...

One day field worker George Cowan brought in a mountain goat covered with nearly a thousand engorged ticks. The researchers plucked the ticks off and decided to see what would happen when they ground them up and injected them into healthy guinea pigs. Every guinea pig got sick and died. The control group were guinea pigs that had been injected with ground-up unfed ticks; they did not get sick.

| Div | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Div | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Div | |||||||||||||||||

|

Dr. Ralph Parker and his group at the Canyon Creek Schoolhouse laboratory became responsible for raising ticks and guinea pigs to feed them. The guinea pigs lived in cages swathed with white cotton as shown in this photo, which was taken in 1931 in Building One. The researchers studied the tick life cycle and fed them on many different animals to see which animals gave the RMSF bacteria to the ticks. They would carefully label the ticks by lot number.

| Div | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||

|

Spencer had discovered that ticks were “a more efficient culture media than the guinea pig” if they went through incubation and feeding first.

- (Quote: "Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever: Experimental Studies on Tick Virus" Roscoe R. Spencer and Ralph R. Parker, Public Health Reports, Vol. 39, No. 48

...

| class | desktop:grid-col-6 |

|---|

...

| id | credit |

|---|---|

| class | credit |

...

- , November 28, 1924, pp. 3027-2040) 1.3 MB

| Div | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||

|

“The feasibility of human vaccination also naturally arises,” he wrote in his 1924 paper describing these studies. And he adds that he tried the vaccine on one human, with no ill effects. The human was himself.

- (Quote: "Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever: Experimental Studies on Tick Virus" Roscoe R. Spencer and Ralph R. Parker, Public Health Reports, Vol. 39, No

...

| Div | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

|

...

| class | grid-row grid-gap |

|---|

...

| class | desktop:grid-col-6 |

|---|

- . 48, November 28, 1924, pp. 3027-2040) 1.3 MB

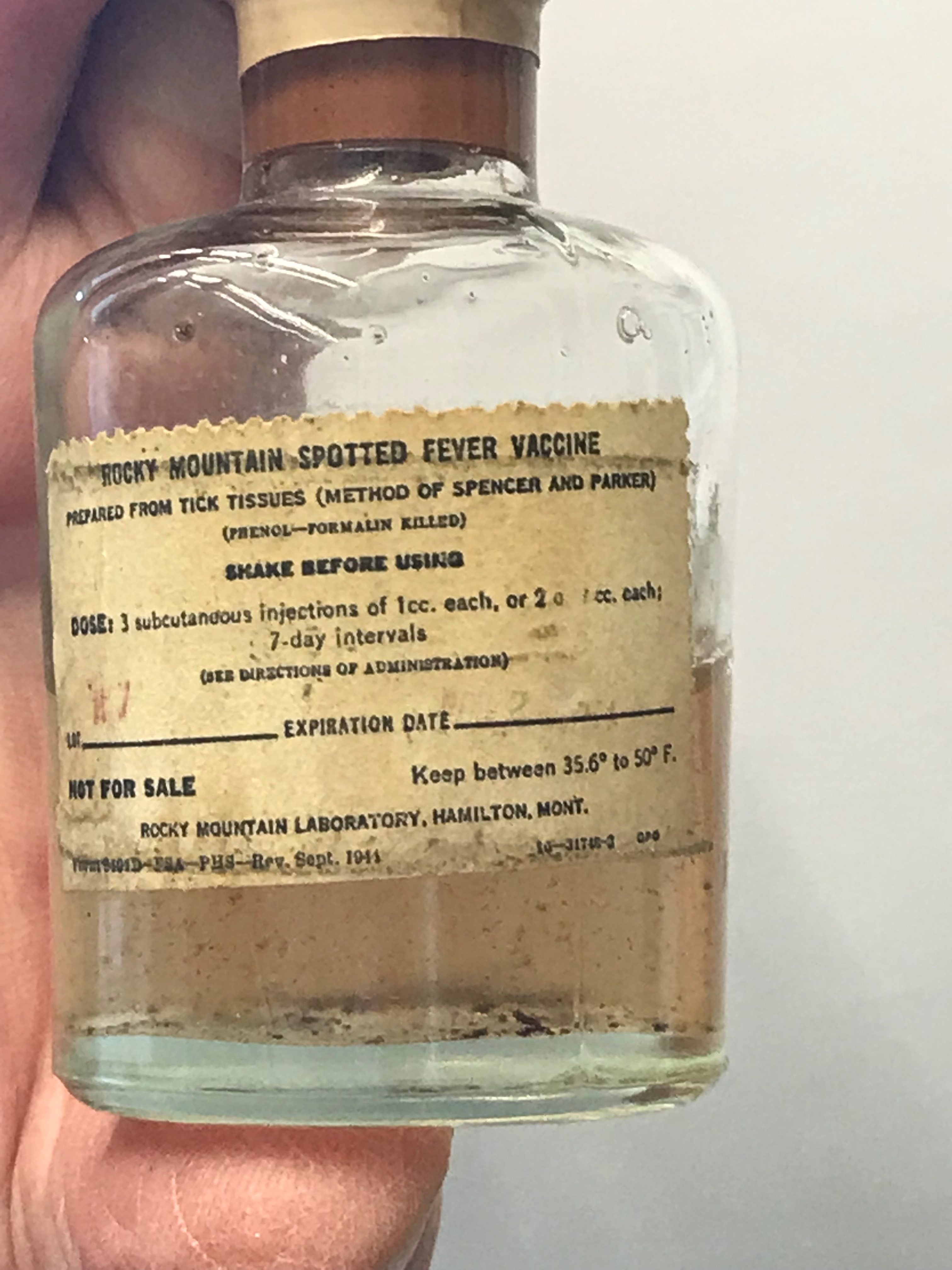

This bottle of Rocky Mountain spotted fever vaccine from the early 1940s represents much scientific work and practical experimentation. There were no strict research protocols for vaccine development and testing in the early

...

19th century. There was no oversight or approvals from the Food and Drug Administration. The Hygienic Laboratory (NIH’s precursor) had regulatory authority, testing commercial vaccines for safety and effectiveness. Spencer worked at the Hygienic Laboratory and was certainly familiar with the tests required to prove that a vaccine worked safely and at what dose it should be given, as well as the standards for producing a safe vaccine. He knew proving that his RMSF vaccine worked would take more than inoculating himself with it.

| Div | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||

|

...