...

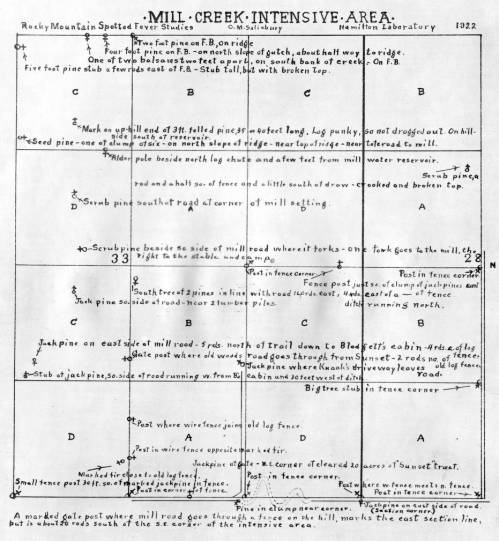

Although it was known that RMSF was caused when the Rickettsia rickettsii bacteria infected a Dermacentor andersoni tick that then bit a human, more questions remained. Was the bacteria spread by other species of ticks? And exactly how did the ticks get infected? To find out where the ticks were picking up the infection and to answer a number of other questions, ticks had to be collected in the wild.

| Div | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| Div | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||

|

How do you get RMSF?

| Div | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||

|

...

Studying the life cycle of ticks provided important pieces of the RMSF puzzle. Knowing the life cycle meant that scientists could study questions such as: When did the ticks pick up the bacteria causing RMSF—was it when they were newly hatched? When they were adults? And was the infection passed on to a new generation of ticks through the eggs? The answers to these questions could be used in control efforts and in developing a new vaccine.

| Div | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

|

...

| Div | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Div | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

|

One day field worker George Cowan brought in a mountain goat covered with nearly a thousand engorged ticks. The researchers plucked the ticks off and decided to see what would happen when they ground them up and injected them into healthy guinea pigs. Every guinea pig got sick and died. The control group were guinea pigs that had been injected with ground-up unfed ticks; they did not get sick.

| Div | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||

|

...