...

| Div | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||

|

| Div | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||

|

| Div | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||

|

| Div | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||

|

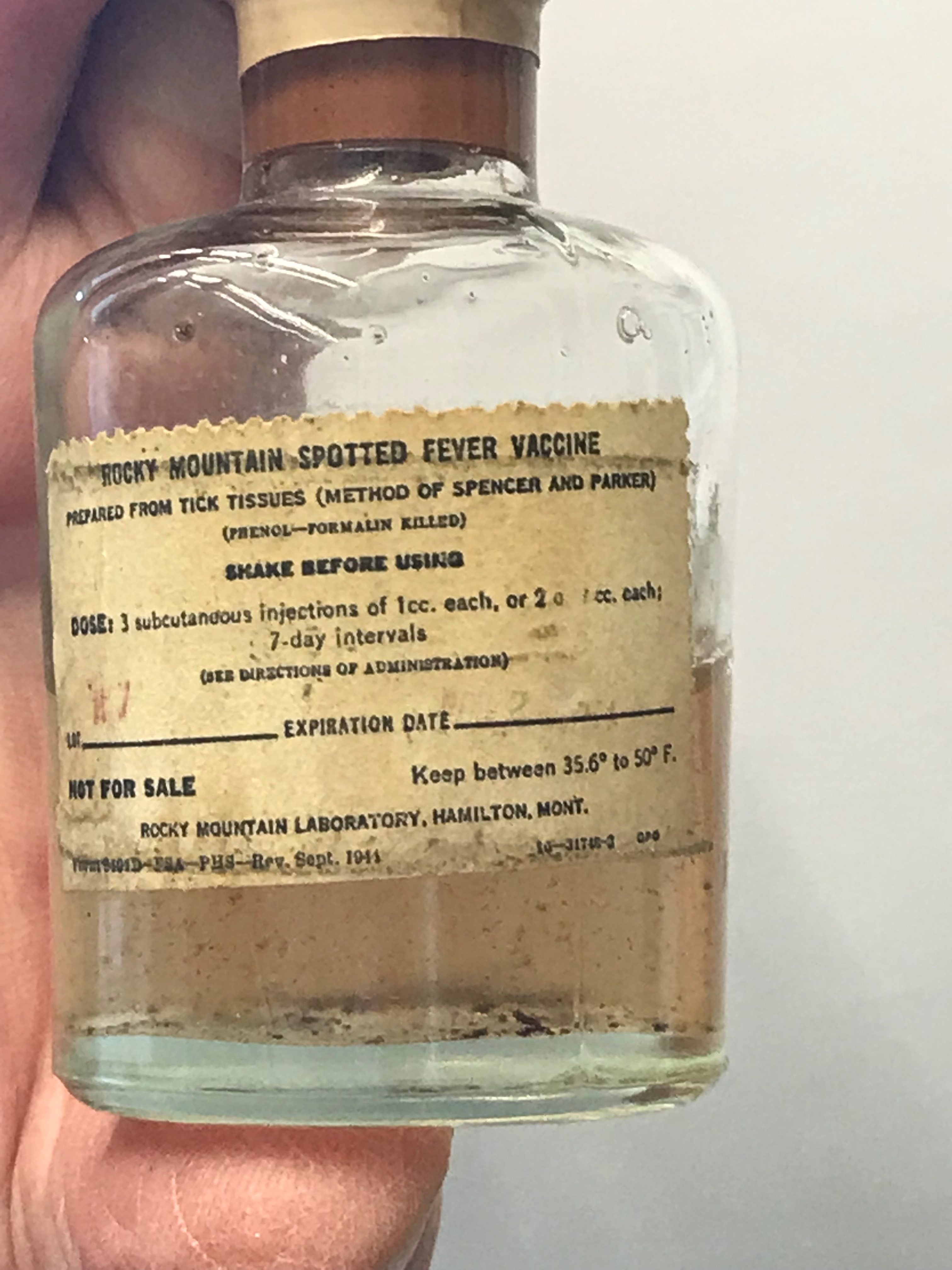

Next was to test the vaccine on people, and the Canyon Creek Schoolhouse laboratory staff became the participants in this early clinical trial. Thirty-four laboratory and field workers were vaccinated, and none had a severe reaction.

There were questions about the vaccine: what was the optimum dose? How long did immunity last? And how long did it take to gain immunity after being vaccinated? That last question was answered in April 1925, when a cattle-dipper for the Montana State Board of Entomology was vaccinated. He came down with RMSF a few days later but recovered. Four other people in the Bitterroot Valley who also got RMSF at the same time, but had not been vaccinated yet, all died. From this unplanned experience, Spencer and Parker learned the time required to gain immunity after vaccination: 10 days

...

| class | desktop:grid-col-6 |

|---|

...

| id | credit |

|---|---|

| class | credit |

...

.

...

Vaccine Production Steps

In 1925, Drs. Roscoe Spencer and Ralph Parker described their method for creating RMSF vaccine. The method would become more streamlined and automated after they moved into the Building One laboratory in 1928 and got better space and equipment than the Canyon Creek Schoolhouse laboratory could provide. These photos include some taken at Building One after the laboratory moved from the schoolhouse.

...