From Schoolhouse to Laboratory

When the Canyon Creek Schoolhouse became a laboratory in September 1921, it was initially rented by the Montana State Board of Entomology for $15 a month because the U.S. Public Health Service was not yet involved in the tick studies. But once the federal agency had sent Dr. Roscoe Spencer and other officers to help the investigation, the laboratory became a field station of the Public Health Service. Citizens of the Bitterroot Valley helped to renovate the schoolhouse into a laboratory with some aid from Red Cross donations. A fence was built to help keep people and non-laboratory animals out—and to keep infected animals in.

The sign on the Canyon Creek Schoolhouse was changed to proclaim the building’s new function as a laboratory under the U.S. Public Health Service, although the day-to-day running of the laboratory was done by Dr. Ralph Parker, a Montana State Board of Entomology employee at the time. Circa 1924.

| Span | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

Image: Rocky Mountain Laboratories, 196 |

The rear of the Canyon Creek Schoolhouse laboratory building on a snowy day. In addition to the animal housing shown here, there was a shed for the scientists’ vehicles and plenty of wood to keep the building warm. Circa 1924.

| Span | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

Image: Rocky Mountain Laboratories, 172 |

In August 1921, a month before the new Canyon Creek Schoolhouse laboratory would open, a Missoulian newspaper reporter wrote that the laboratory would be run by Dr. Ralph Parker, who would be “vested with unlimited authority by the government, the state and the county, and who will not be denied any and all assistance on the part of local people that it may be possible for them to give.” The lab would also employ not just researchers but a stenographer, a bookkeeper, and a maintenance crew to see that all was kept safe. The laboratory was much more spacious and solid than any so far used for this research.

- Quote from “Property Leased for Tick Fever Laboratory,” The Missoulian, Aug. 21, 1921.

Dr. Ralph Parker peered into his dissecting microscope in his office/laboratory at the Canyon Creek Schoolhouse laboratory, circa 1921. A monocular microscope sat beside him. The laboratory had electricity and large windows for light. The sink was in an indentation in the wall behind him, under a shelf of chemical bottles, with the towels hung on the wall. A map of Rocky Mountain spotted fever’s occurrence sat on a table in the foreground on the right.

| Span | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

Image: Rocky Mountain Laboratories, 471 |

| Div | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

|

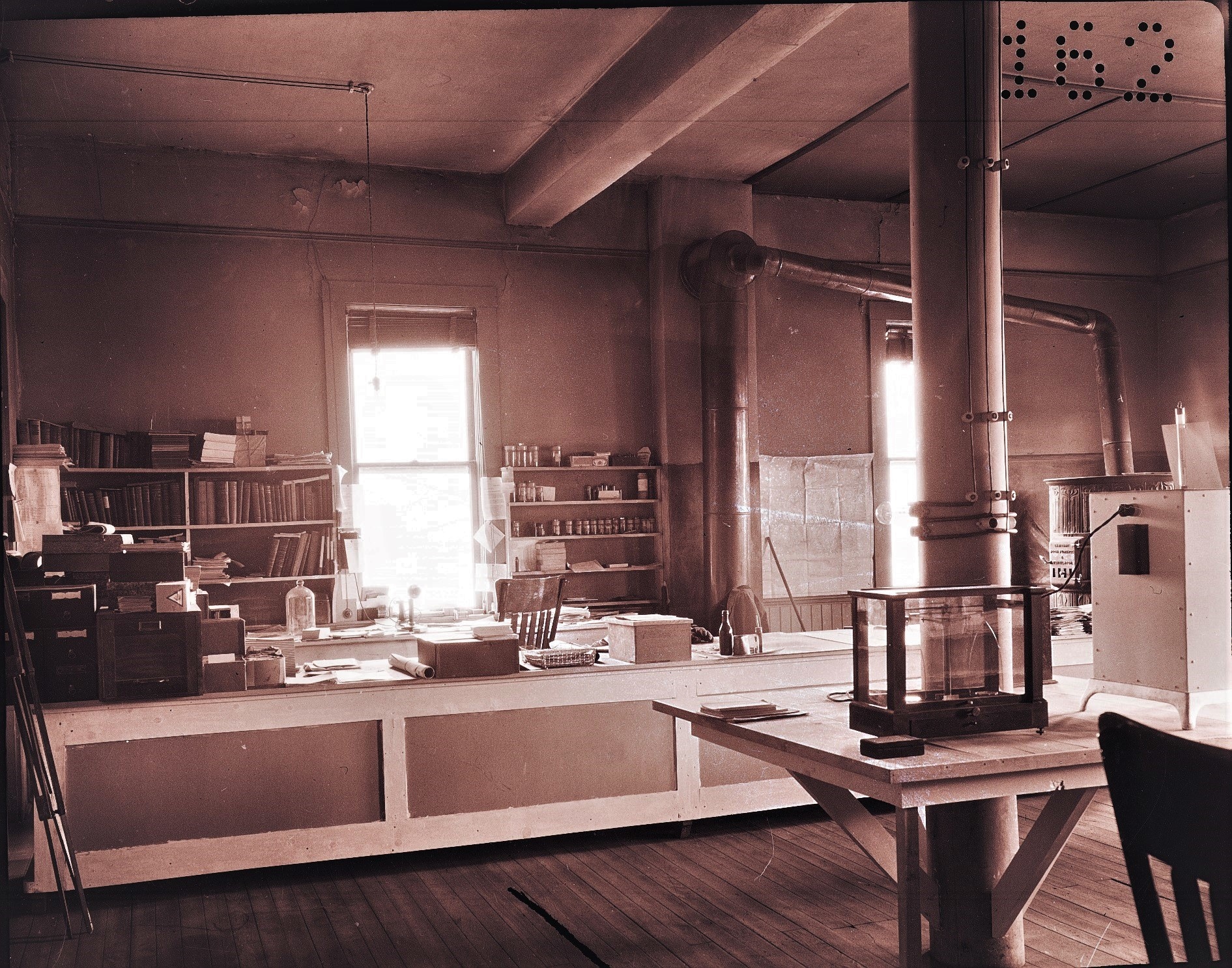

The far corner of the office/laboratory, circa 1921. Rows of chemicals stood on shelves above the map of Rocky Mountain spotted fever cases. Next to the glass bell jar instrument cover were likely metal canisters containing pipettes. The white unit on the counter-top is either a double-walled hot air sterilizer or an oven for drying glassware. Next to that a copper retort is connected by its neck to a zinc condenser. The liquid in the retort was heated and the condensation ran into the condenser, where it was cooled to make a refined liquid. This was an old-fashioned way to do laboratory distillations even in the 1920s, but it produced a good amount of liquid. The Canyon Creek Schoolhouse laboratory would have had to fill out special paperwork for the U.S. Treasury certifying why they were using it; such distillation set-ups were commonly used as stills by bootleggers during the years of Prohibition.

| Span | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

Image: Rocky Mountain Laboratories, 484 |

| Dive | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The researchers developed their own equipment over the years at both the Canyon Creek Schoolhouse Laboratory and the later Building One laboratory building. They adapted and invented equipment to both keep them safe from tick bites and to make their jobs a little easier. Dr. Robert Cooley, head entomologist, took these photos of some of their inventions in 1931 after they had moved to Building One.

These cabinets were designed to heat the clothes that the workers wore in the laboratory to a temperature high enough to kill any ticks hiding in them.

| Span | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

Image: Rocky Mountain Laboratories, 215 |

Grinding so many ticks by hand would have been tiring; it would also have slowed down production of the Rocky Mountain spotted fever vaccine for use around the United States. So the researchers used an electric motor (right) to drive a crank and shaft device that moved a pestle in a mortar (bowl on stand on left). This machine was a prototype for later automatic tick grinders that could handle increased production without injuring anyone’s elbow.

| Span | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

Image: Rocky Mountain Laboratories, 231 |

Several “guns” were developed too. One separated adult living tick parasites from the tick nymphs they had destroyed. This one was used to separate adult ticks from their nymphal skins. These tools were also an attempt to increase the efficiency of making the Rocky Mountain spotted fever vaccine.

| Span | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

Image: Rocky Mountain Laboratories, 302 |