Can We Prevent, Treat, or Cure It?

The third question that medical researchers try to answer is the most important, and often depends on the answer to the question, "What causes it?" For Gaucher disease, physicians initially attempted to address the symptoms that accompany the disease. They removed enlarged spleens, and performed liver transplants, blood transfusions, and orthopedic procedures. Only bone marrow transplantation for people with Type I Gaucher disease was sometimes successful. To be truly successful, a treatment would have to address the cause of the disease, not just the symptoms.

In 1966, Dr. Roscoe Brady suggested a therapy for Gaucher disease based on replacing the enzyme. Using human placentas, Dr. Peter Pentchev of Dr. Brady's team isolated a tiny sample of purified glucocerebrosidase. In 1973, two patients received this enzyme; because of the good biochemical results, Brady decided to develop a procedure to obtain larger quantities of the enzyme for further clinical trials.

A large-scale purification method was completed in 1977. The enzyme had to be treated with an alcohol to make it stick to the purifying columns. But this preparation of the enzyme produced inconsistent results during clinical trials. The alcohol had removed a lipid (fat) that activates the enzyme and targets it to the affected cells, called macrophages. Dr. Brady's challenge was now to get the purified enzyme into the targeted cells.

A diagram of Native mannose term diagram

Dr. Peter Pentchev

Dr. Roscoe Brady examining a young child

About this time, two facts became known. First, the enzyme has sugar side-chains attached to amino acid backbone of its structure. Second, macrophages react with enzymes whose sugar chains end with the sugar called "mannose." The problem was that the mannose on the sugar side chains of glucocerebrosidase was inside of the chains, not on the end of the chains. The mannose therefore could not interact with macrophages. Dr. Brady's team needed to develop a method to strip off some of the sugars on the ends of the side chains to expose the mannose, which would allow the enzyme to bind to the macrophages.

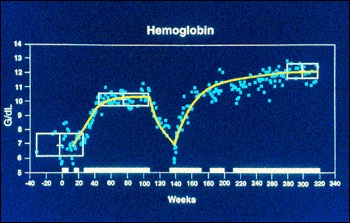

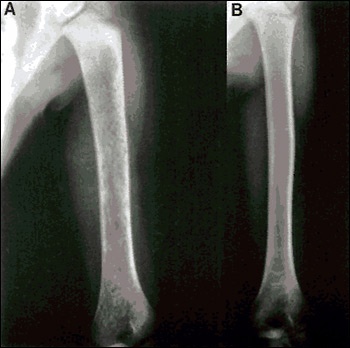

In the first clinical trial with macrophage-targeted glucocerebrosidase, eight people with Gaucher disease received a fixed dose of the modified enzyme. Only the smallest one - a child - experienced beneficial effects. His hemoglobin and platelet counts increased; the size of his spleen and liver decreased; and the damage to his bones lessened. The other seven people were adults and had not received enough of the enzyme to improve their condition.

Brady's team then selected a different dose amount of replacement enzyme for a trial of twelve people with Gaucher disease. All of these people had strikingly good clinical responses within a few months. For example, their height and weight increased; their anemia improved; their liver and spleen sizes decreased; and their bone damage lessened. Because of these findings, macrophage-targeted glucocerebrosidase was approved as a specific treatment for Gaucher disease by the Federal Drug Administration on April 5, 1991. Enzyme replacement therapy worked.

In a few short years, people with Gaucher disease were able to receive the enzyme replacement therapy at home. Enzyme replacement therapy is an effective treatment for most people with Type 1 Gaucher disease.

Dr. Brady is conducting genetic research to provide a cure for all people with Gaucher disease. At the National Institutes of Health in May 1995, a young man with Gaucher disease received the first gene therapy for that disease. He received back his own cells into which the correct genes for making the enzyme glucocerebrosidase had been inserted. He had no adverse reaction, proving the safety of the procedure. Current trials are attempting to determine the efficacy of gene therapy for Gaucher disease.

Gene Therapy Experiment

Hemoglobin Chart

Before and after X-Rays