Growth Years 1953-1969

| Div | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

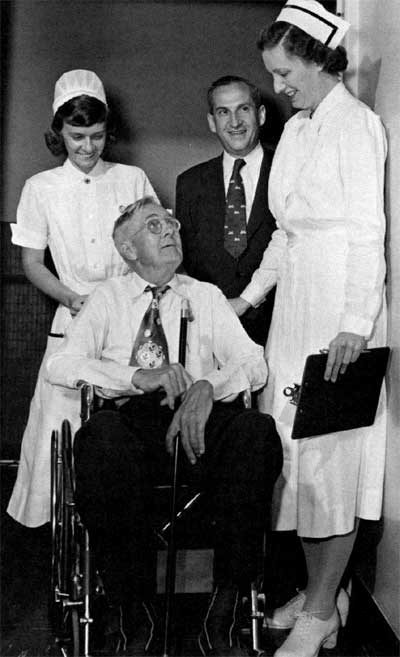

In July 1953, Charles Meredith, a 67-year-old farmer, was admitted as the first patient. Under the care of Dr. Roy Hertz (rear), he underwent hormone therapy. |

Getting Underway

Under the administration of the first operating director of the Clinical Center, Dr. John A. Trautman, patient admissions followed at a steady pace. By January 15, 1954, there were 115 occupied beds on seven nursing units.

| Footnote |

|---|

Minutes, Scientific Directors meeting, January 13, 1954, box 3, RG 443. |

The original patient cohorts were largely ambulatory and not acutely sick, reflecting Sebrell’s desire that most “will leave the Clinical Center in better physical shape than when they entered.”

| Footnote |

|---|

Minutes, Scientific Directors meeting, April 2, 1952. |

...

|

...

|

| Footnote |

|---|

Washington Post, August 9, 1953, lB. |

Of these, one case of thrombotic occlusion surgically removed was presented as a “complete cure” at the first Combined Clinical Staff Conference on January 20, 1954.

| Footnote | |

|---|---|

Typescript, Proceedings of the Combined Clinical Staffs, NIH Clinical Center, January 20, 1954, presentation by Dr. James Wyngaarden, in box Miles, Institutes, folder Clinical Center, 1953, HMD, NLM

|

Medical policies in the fledgling hospital were set by the Medical Board, composed of institute clinical directors and chairs of the operating medical departments, who met to advise the Clinical Center director. Projecting the Clinical Center as “the ‘ideal hospital’ of the future,” the Board established broad responsibility for patient welfare. Study patients were to be considered members of the research team, entitled to “full understanding of the investigation contemplated” and to free care for the duration of the research. Investigators were enjoined from imposing citizenship or residence requirements. The Board also disallowed “any restriction based on race, creed, or color.”

...

| Footnote |

|---|

Sebrell, oral history, pp. 96-97. |

retired in August 1955. NIH leadership passed to Dr. Shannon, who vigorously exploited opportunities for expanded research, administration, and funding.

| Footnote |

|---|

Minutes, NAHC meeting, 10/27-28/55, Supp. II,2,4, in box 3, Subject File, RG 443. |

...

Responding to Changing Times

| Div | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

...