Growth Years 1953-1969

The very best definition I have ever found for a hospital is the old Quaker expression, “bettering house.” It is a simple, honest term, which sums up the whole reason for being of all our health professions as they work together on the hospital team.

Jack Masur, speech to Washington State Hospital Association, Spokane, October 19, 1955

As Dr. James Shannon remembered it, starting up the Clinical Center took “a very rough couple of years.”

1

There was no established culture of medical practice supporting clinical research at Bethesda, no public funding commitment for basic science breakthroughs or for training the next generation of clinicians and scientists, and no clear paths to the next level of biomedical knowledge. The initial barriers were political. President Dwight D. Eisenhower took office in January 1953, determined to scale back federal health spending. His administration’s budget for the PHS fiscal year 1954 was $219 million, a reduction of $51 million from the previous administration’s projection.

2

The Clinical Center’s incomplete professional staff complement of 245 scientists and clinicians was frozen, and the April 1 opening was postponed for budgetary reasons.

3

When Oveta Culp Hobby, the new Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare, visited the building in April, she asked NIH Director William H. Sebrell whether the facility could be kept closed as an economy measure. Sebrell assured her that the political costs would be prohibitive, and the administration proceeded with plans to activate the first 150 beds on July 1.

4

Dedication ceremonies marking the opening of the first 26-bed nursing unit were held the following day in sweltering, 100-degree heat. In her remarks, Secretary Hobby invoked the promise of “cures as yet unthought of” and praised Congress for its nonpartisan willingness to fund medical research. “Scientific truth knows no politics,” she averred, and dedicated the Clinical Center to “the open mind of research.”

5

Oveta Culp Hobby, soon to be designated Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare, visiting the Clinical Center building on April 6, 1953. With her are (l. to r.) CC Director John A. Trautman, Surgeon General Scheele, and NIH Director Sebrell. Courtesy of Parklawn Library, Public Health Service.

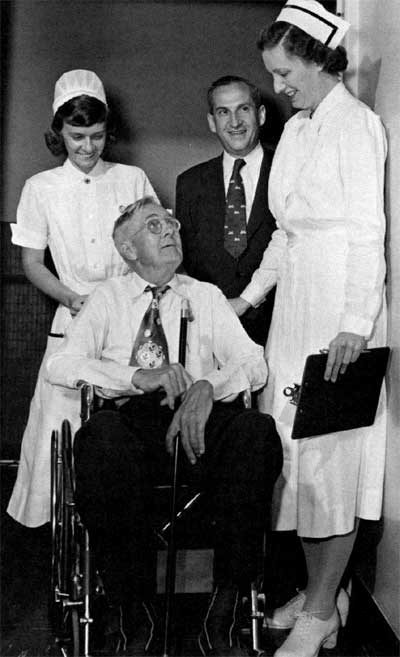

In July 1953, Charles Meredith, a 67-year-old farmer, was admitted as the first patient. Under the care of Dr. Roy Hertz (rear), he underwent hormone therapy.

Getting Underway

Under the administration of the first operating director of the Clinical Center, Dr. John A. Trautman, patient admissions followed at a steady pace. By January 15, 1954, there were 115 occupied beds on seven nursing units. 6 The original patient cohorts were largely ambulatory and not acutely sick, reflecting Sebrell’s desire that most “will leave the Clinical Center in better physical shape than when they entered.” 7 Of 23 admissions to Patient Care Unit 12E in the first four weeks of activation, nine were cancer patients transferred from the endocrinology branch clinic at George Washington University Hospital, which NCI had set up under Dr. Roy Hertz in 1949. Six other admissions were involved in arthritis or diabetes studies conducted by the fledgling National Institute of Arthritis and Metabolic Disorders (NIAMD), and seven others, all ambulatory, were Heart Institute patients participating in arteriosclerosis investigations. 8 Of these, one case of thrombotic occlusion surgically removed was presented as a “complete cure” at the first Combined Clinical Staff Conference on January 20, 1954. 9 Medical policies in the fledgling hospital were set by the Medical Board, composed of institute clinical directors and chairs of the operating medical departments, who met to advise the Clinical Center director. Projecting the Clinical Center as “the ‘ideal hospital’ of the future,” the Board established broad responsibility for patient welfare. Study patients were to be considered members of the research team, entitled to “full understanding of the investigation contemplated” and to free care for the duration of the research. Investigators were enjoined from imposing citizenship or residence requirements. The Board also disallowed “any restriction based on race, creed, or color.” 10 The political obstacles to Clinical Center growth were overcome at the close of Eisenhower’s first term, largely as a result of the Salk polio vaccine controversy and reemergent congressional pressure for biomedical research spending. NIH had limited its involvement to long-term, live virus studies until January 1953, when the private National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis announced a killed-virus cure and requested federal oversight for vaccination trials. Assistant Director Shannon and leading NIH virologists attempted to bring order to the precipitate rush to mass inoculation in 1954, but when faulty vaccine licensed by the NIH Laboratory of Biologics Control caused 209 new polio cases in April 1955, the administration convened a special, NIH-led committee to ensure the vaccine’s safety and to complete the program. 11 Secretary Hobby took responsibility for the faulty vaccine and resigned. Her successor, Marion P. Folsom, disavowed the policy of retrenchment and resolved to step up the search for disease cures. 12 Director Sebrell, uncomfortable with new and more expansive national responsibilities, 13 g. 14 Working closely with Senator Lister H. Hill, who chaired both the Appropriations Health Subcommittee and the full Labor and Public Welfare Committee, Shannon persuaded Congress to double the NIH budget in the spring of 1956. A new era of expansion was thereby inaugurated. 15

Cures and Breakthroughs

At the hospital, Dr. Trautman left the directorship in June 1954 to take charge of a 1,000-bed PHS facility in Fort Worth, Tex. His successor, Dr. Donald W. Patrick, had previously headed the PHS hospital in Baltimore, where the Heart and Cancer Institutes had operated clinical wards. 16 Under Dr. Patrick, the pace of patient referrals and admissions was slower than expected — only 332 beds had been activated by January 1955. At the same time, research interest intensified, and clinical advances began to proliferate. A National Science Foundation survey 17 conducted later that year showed dramatic early results for clinical research, with curative therapies prominently featured. The National Institute of Arthritis and Metabolic Diseases (NIAMD) claimed a “spectacular clinical response" in 15 rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with the steroids prednisone and prednisolone. The Cancer Institute reported success in managing solid tumors with chemical agents and in inhibiting other tumors with intravenous androgen and estrogen. The Heart Institute developed an aortic valve prosthesis, and Mental Health determined the metabolic fate of LSD and other mind-altering drugs. Neurological Disorders and Blindness relieved seizures in 50 epileptic patients with glutamic acid treatments, while National Microbiological Institute clinicians restored sight to 25 patients with toxoplasmic uveitis. Dental Institute studies of the effect of ingested fluorides on human physiology allowed water fluoridation programs to go forward.

Masur Returns

Despite the favorable prognosis for clinical advances and intramural funding, internal obstacles attributable to decentralization forced the hospital to restrict growth in 1957 and shift resources to the development of central services. 18 The major problem, which would recur throughout the next two decades, was an acute shortage of nurses. The patient load as of March 1, 1956, required 363 nurses, but only 269 full-time and 19 part-time nurses were on duty, reflecting a turnover rate of two resignations for every three hires. 19 Director Shannon went before Congress in February 1956 to explain that full operation — 510 activated beds — would not be reached for another year. 20 The actual situation on the wards was more serious, for the average daily census of occupied beds remained below 300 for most of fiscal year 1956. 21 The nursing services, at this point organized into a Nursing Department but still responsible to the institutes, were stressed by diagnostic regimens requiring five times as many tests as in general hospitals, and by a mushroom growth in follow-up examinations. 22 Seeking a more vigorous response, Dr. Shannon in October reappointed Dr. Masur as Clinical Center director. 23 Remembered for his “endearing belligerence,” 24 Masur employed a leadership style that was at once strong-willed, pragmatic, and compassionate. During his 13-year tenure as director, he emphasized “traditions of excellence” 25 in clinical service to make the Clinical Center a national model. His frequent refrain, “This institution doesn’t follow standards; it sets them,” 26 underscored his keen interest in pragmatic solutions to operational problems. Among his early credits were organizing the Clinical Associate alumni program and setting standards for the normal control program. He accurately perceived that a minority of NIH basic scientists resented the priority accorded to clinical applications and avoided participation in Clinical Center activities. 27 But he was less interested in achieving a synergy between scientists and clinicians than in building up clinical services and enforcing the discipline that researchers and staff needed to observe in a patient-care environment. 28

Meeting the Challenges

As the hospital reached full occupancy in 1958, a process of seasoning began. By adjusting to a variety of stresses and strains, the operating departments gradually perfected the delivery of clinical services.

The Nursing Department faced rising acute care requirements, particularly an influx of more critically ill patients and 234 major operations performed that year in the Clinic of Surgery. 29 In response, a postoperative care unit was planned and opened that year, and preparations were made to shift the nonprofessional work load from professional nurses to attendants and technicians. 30 The program did not cover the staffing gap, however, because of the curtailment of diploma schools and diminishing numbers of practical nurses. Actual nursing positions filled declined from 617 in 1961 to 479 in 1970, and average hours of care per patient per day dropped from 6.13 to 4.82 as the patient census rose steadily. 31 Quality care was maintained on the wards by “a greater understanding of mutual dependence” between physicians and nurses and by “increasing efforts of physicians to teach and interpret routines to nursing service personnel.” 32 Under Chief Louise C. Anderson, active collaboration by nurses in research protocols became an important feature of nursing activities.

Clinical Pathology was beset by more complex operational difficulties in 1958. The test rate neared 30,000 per month, three times the planned rate at full activation. Technologists were performing 40 procedures daily, twice the normal work load, and the department chief, Dr. George Z. Williams, asked to limit intake. 33 A Medical Board Steering Committee declined to limit investigators’ use of diagnostic services and put its faith in automatic instrumentation, while the institutes remained unwilling to reallocate nine modules of laboratory space. 34 Cast back on its own resources, the department under Williams undertook research to develop new analytic tests and to investigate areas of hematology, clinical chemistry, and microbiology bearing on analytic problems. This led in 1965 to early adaptation of computerized data processing for pathology procedures, a national leadership role Williams saw as essential to the Clinical Center mission. With the support of Congress in 1966, a model laboratory was developed. 35 A similar reliance on developmental research and innovative diagnostic technology characterized the radiology and radiography services, housed before 1965 in the Diagnostic X-ray Department. Collaborative efforts with intramural technologists in 1964 produced two state-of-the-art apparatuses: a tomography system utilizing a moving x-ray, and a tetra scanner that delivered a complete brain scan in 22 minutes. 36 Radioisotope use quickly became generalized in clinical studies, and in 1966 the Department of Nuclear Medicine was set up alongside Diagnostic Radiology to develop and service new diagnostic modalities. By 1968, television applications of the gamma scintillation camera were allowing heart surgeons to monitor blood flow in occluded arteries. 37

A Revolution in Clinical Research

The clinical services flourished after 1960 largely because Congress was committed to raising health care spending nationwide to $2 billion in 10 years. However, Director Shannon in 1958 and 1959 tried to enforce a no-growth budget on the Clinical Center, in the belief that, “The era of rapid expansion of intramural programs at Bethesda has come to an end.” 38 Senator Hill and Representative Fogarty would not accept a no-growth strategy, and they succeeded in raising the NIH’s budget by about $150 million in 1960 and again in 1961. Under this fiscal sunshine the research revolution resumed. 39 Cancer chemotherapy studies received a large extramural appropriation, spurring intramural investigators who developed a four-drug cure for childhood leukemia and a “Life-Island” isolation system to protect debilitated patients from infection. 40 An upsurge in cardiovascular studies followed the opening of a new surgical suite in 1963. Heart Institute clinicians successfully tested alpha-methyl DOPA on patients with hypertension, and surgeons under Dr. Andrew Morrow performed thousands of operations relieving stroke symptoms in human patients and repairing congenital defects and atherosclerotic damage. The blood bank emerged as a separate department in 1965; a platelet separator was developed; and investigators Harvey Alter and Baruch Blumberg isolated the Australia antigen in leukemic blood samples. 41

Serving Unique Patients

Patient services became more intensive after December 1962, when bed occupancy reached 87% and average length of stay fell from 45 to 30 days. 42 Dr. Masur, who served a concurrent term as president of the American Hospital Association in 1961, sought to establish national standards for patient care at the Clinical Center. After the thalidomide controversy, Masur proposed a joint study with two other medical centers to build a data bank on adverse patient reactions to new drugs. 43 This project failed to materialize, but Masur’s long-term interest in limiting therapeutic hazards for normal patients brought an end to prisoner testing at the hospital and established special consent procedures for volunteers in investigational drug trials. 44 “We must strike a better balance between the wonders of technology and the wonders of human kindness,” he told a Yale lecture audience in 1962. 45 The inpatient wards were actively serviced by Rehabilitation and Social Work therapists, with extensive recreation activities sponsored by Patient Activities and Red Cross volunteers. At the beginning of the peak period for inpatient services, 1965-1968, the annual report claimed that the hospital’s highest achievement lay in creating an atmosphere of “personal warmth” for the research patient. 46 The effect was quite durable. When Newsweek columnist Stewart Alsop was admitted for treatment of subacute leukemia in 1971, he noted in his journal, “Amazing how nice almost everybody is.” 46

Responding to Changing Times

In the years after 1965, expansion leveled off for NIH as a whole. A mature institution emerged, with a fresh overlay of training and education responsibilities added by the administration of Lyndon B. Johnson. 47 For the Clinical Center this meant growing interaction with regional clinical research centers, partially funded by the NIH Division of Research Resources, as sources for patient referrals and opportunities for clinical trials. Johnson reorganized the PHS to put NIH directly under White House control, and he also recruited Masur as a Great Society spokesman to promote the acceptance of Medicare and to push for a greater distribution of the fruits of medical research. 48 Visiting the Clinical Center on August 9, 1965, Johnson publicly signed the Health Research Facilities Amendments Act, which allocated $230 million for research contracts and construction grants to regional medical centers. 49 Subtly, the Clinical Center adopted the administrative requirements involved in servicing the expanded health system. The 1967 mission statement promised “opportunities for young physicians and other professionals to prepare for careers in medical or related research.” 50 The hospital continued to grow, as 24 beds were added for the new National Institute of Child Health and Human Development between 1966 and 1968. But some NCI patients were now housed in local motels, family-style meals were being replaced by tray service on the wards, and nurses noted “a great many more sick patients in the house.” 51 Slowly the hospital was becoming more of a service center and less of a self-contained chronic care community.

The critical point in this transformation came in 1968, as the Vietnam War reached its crisis and President Johnson announced his intention to leave office. The administration could not fund its Great Society programs for fiscal 1969. In July the budget was reduced from $30 billion to $24 billion, and a 10 percent surtax was imposed to keep the government solvent. Masur’s staff recognized that federal services would be reduced, that personnel vacancies at the hospital would go unfilled, and that a period of “lean years” lay ahead.

52

With the retirements of Dr. Shannon as NIH director in September and Senator Hill as chief sponsor of medical research in November, the federal science enterprise was for the moment a political orphan.

53

Dr. Masur’s sudden death from acute myocardial infarction on March 8, 1969, was a tragic loss, which closed two decades of political good fortune, scientific brilliance, and clinical elan. No other director would style himself “superintendent of the hospital,”

54

and no other hand would influence as critically the institution’s development and daily life. In a time of great turmoil in American society at large, his passing left the Clinical Center a future replete with both promise and uncertainty.

Director Trautman and the Red Cross volunteers, valued for bringing a personal touch to patient service.

Courtesy of Parklawn Library, Public Health Service.

Nurse attending a patient in Life Island, a bacteriologically controlled environment. October 1964

Footnotes

- Shannon, Reminiscences, CUOHP, 32. ↩

- Rough notes on Scheele testimony, House Appropriations Subcommittee, March 3,1954, attached to minutes, April 1, 1954, Institute Directors Meeting, in Subject File, Office of the Director, NIH, box 3, RG 443. ↩

- Topping, "The United States Public Health Service Clinical Center for Medical Research", pp. 544; NAHC minutes, February 20-21, 1953, Subject File, box 4, RG 443; memorandum, Sebrell to All NIH Employees, March 4, 1953, Historian’s File, HMD, NLM. ↩

- Sebrell, oral history, pp. 57, 160. ↩

- Hobby speech text, July 2, 1953, Office of the Director, NIH, in Historian’s Office File, HMD, NLM. ↩

- Minutes, Scientific Directors meeting, January 13, 1954, box 3, RG 443. ↩

- Minutes, Scientific Directors meeting, April 2, 1952. ↩

- Washington Post, August 9, 1953, lB. ↩

- Typescript, Proceedings of the Combined Clinical Staffs, NIH Clinical Center, January 20, 1954, presentation by Dr. James Wyngaarden, in box Miles, Institutes, folder Clinical Center, 1953, HMD, NLM. ↩

- Minutes, Medical Board meetings, May 25, 1953 and June 6, 1953, and Report of Clinical Research Committee, May 25, 1953, Medical Board minutes file; statement, Admission and Discharge Policies for the Clinical Center, May 8, 1953 box 3, Subject File, RG 443. ↩

- Jane E. Smith, Patenting the Sun: Polio and the Salk Vaccine, New York: William Morrow, 1990, pp. 175-87, 248-60, 295-300, 359-68. ↩

- Congressional Research Service, Congress and the Nation, 1945-1964, pp. 1136-37. ↩

- Sebrell, oral history, pp. 96-97. ↩

- Minutes, NAHC meeting, 10/27-28/55, Supp. II,2,4, in box 3, Subject File, RG 443. ↩

- Shannon, Reminiscences, CUOHP, 35-39; Congress and the Nation, 1945-1964, p. 1125; Bruce Merchant, “Clinical Research in the National Institutes of Health,” senior thesis, Nebraska Wesleyan University, 1957, pp. 19-20. ↩

- “Conference of the Combined Clinical Staff,” 7/1/54, business session, pp. 3-6, NIH Library. ↩

- Data Assembled for the Special Committee on Medical Research of the National Science Foundation, Bethesda: NIH, 1955, NIH Library, no page numbers. ↩

- Proceedings of the Combined Clinical Staff Conference, April 11, 1957, pp. 1-2, NIH Library. ↩

- Memorandum, Executive Officer to Director, NIH, “Study of Nursing Activities..., March 1, 1956, Subject Files, folder Clinical Center Nursing Study, 1956, box 25, RG 443. ↩

- U.S. House, Hearings, 84th Congress, 2nd Session, Appropriations Subcommittee, Depts. of Labor/HEW, FY 1957, pp. 502-5. ↩

- HEW, “Program Operations Report to the Secretary,” April-June, 1956, pp. 31-36, Subject File, box 20, RG 443. ↩

- Minutes, Medical Board, January 11, 1955, meeting, pp. 1-2; Merchant, “Clinical Research,” p. 37; HEW, “Program Operations,” April-June 1956, p. 36. ↩

- Shannon, Reminiscences, CUOHP, 31. ↩

- Sebrell remarks, dedication ceremony, June 25, 1953, NIH Historian’s Office papers, HMD, NLM. ↩

- Proceedings of the Combined Clinical Staff Conference, April 11, 1957, pp. 7-8. ↩

- Informal notes, Medical Board, November 6, 1957 meeting. ↩

- Merchant, “Clinical Research,” 68-69, citing December 11, 1956 interview. For the viewpoint of those scientists who feared clinical applications would misdirect basic science, see Arthur Kornberg, For the Love of Enzymes: The Odyssey of a Biochemist, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1989, p. 128. ↩

- Masur, Reminiscences, CUOHP, 28-29. For the contrasting approach, see James A. Shannon, “The Relationship of Laboratory Research to Clinical Investigation,” address delivered 5/21/59, in NIH Historian’s Office File, HMD, NLM. ↩

- Annual Report of Program Activities, Clinical Center, 1958, Nursing Dept., pp. 1-5, NIH Library; Medical Board, “Professional Services Review,” August 27, 1957, minutes file. ↩

- Minutes, Clinical Directors meeting, February 11, 1959, Acc. 443-62-D-0064, box 100, Washington National Record Center. ↩

- Annual Report of Program Activities, Clinical Center, 1966-67, Nr 2,4; Staffing figures attached to minutes, Clinical Directors meeting, January 19, 1970, box 3, RG 443, National Archives. ↩

- Annual Report of Program Activities, Clinical Center, 1966-67, Nr 4. ↩

- Minutes, Medical Board meeting, March 11, 1958; rough notes, same date, attached; memorandum, Williams to Shannon, November 28, 1958, “Estimate of Program Activities, FY 1961-1965,” box 103, Task Force folder, RG 90, WNRC. ↩

- Steering Committee Report, May 13, 1958, with rough notes, Medical Board minutes file. ↩

- Jerome B. Block, Clinical Center Contributions to Research, November 20, 1972, Historical File, Clinical Center Communications Office; Annual Report of Program Activities, Clinical Center, 1966-67, CP-1. ↩

- News From NIH, publication of NIH Office of Research Information, March, 1965, Department of Diagnostic Radiation historical file; Annual Report of Program Activities, Clinical Center, 1964-65, serial 35, pp. 1-3. ↩

- Annual Report of Program Activities, Clinical Center, 1966-67, NM 1-14; Annual Report..., 1967-68, OD 36. ↩

-

Shannon to Institute Directors, January 14, 1958, “Means of Gradually Re-orienting

Intramural Research Programs,” Scientific Directors Meeting file, box 105, RG 90,WNRC: Report, Office of the Director, NIH, “Intramural Research Activities.. to 1970,” April 1959, box 104. ↩ - Congress and the Nation, 1945-1964, pp. 1139-41. ↩

- Department of HEW, Research for Health, PHS Pub.1205, Washington, DC: GPO, 1964,5-6; Annual Report of Program Activities, Clinical Center, 1964-65, Nursing Dept., p. 3. ↩

- Research for Health, pp. 11-13; Annual Report of Program Activities, Clinical Center, 1964-65, Blood Bank Dept., pp. 1-4. ↩

- Minutes, Medical Board meeting, December 11, 1962, p. 3. ↩

- Minutes, Medical Board meetings, September 25, 1962, and October 9, 1962. ↩

- Annual Report of Program Activities, Clinical Center, 1966-67, OD-2; minutes, Normal ControlsCommittee meeting, April 24, 1963, 1-5; minutes, Medical Board meetings, July 28, 1964, October 11, 1966, and November 8, 1966. ↩

- New Haven Journal Courier, May 4, 1962. ↩

- Annual Report of Program Activities, Clinical Center, 1964-65. ↩ ↩

- NIH Study Committee, Biomedical Science and Its Administration: A Study of the National Institutes of Health, Washington, DC: GPO, 1965, pp. 8-9; James A. Shannon, “The Advancement of Medical Research: A Twenty-year View of the National Institutes of Health,” Journal of Medical Education, 42: 102-108 (February, 1967). ↩

- Congress and the Nation, vol. II, 667-72, 680-90; Masur speech to New England Hospital Assembly, March 28, 1966, excerpts in Providence Journal, March 29, 1966; New York Times, May 30, 1966. ↩

- NIH Record, August 24, 1965. ↩

- Annual Report of Program Activities, Clinical Center, 1966-67, OD-1. ↩

- Annual Report of Program Activities, Clinical Center, 1965-66, OD-5, Nr 3; minutes, Medical Board Meeting, June 18, 1965; minutes, Clinical Directors meeting, September 16, 1967, box 3, RG443. ↩

- Minutes, Clinical Center staff meeting, July 2, 1968, box 3, RG 443; Joseph Califano, Jr., The Triumph and Tragedy of Lyndon Johnson: The White House Years, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1991, pp. 253-73. ↩

- Hamilton, Lister Hill; Statesman from the South, pp. 275-81. ↩

- Masur, Reminiscences, NLM OHP, pp. 27-28. ↩