Introduction

Fluorescence in medicine has enabled researchers to see the invisible.

In the 1950s the NIH's Dr. Robert Bowman developed a sensitive instrument-called the spectrophotofluorometer, or "SPF"-that allowed scientists to use fluorescence as a way to identify and measure tiny amounts of substances in the body. This scientific breakthrough, invented almost half a century ago, is still used today in AIDS research and the Human Genome Project.

Spectrophotofluorometer

Dr. Robert Bowman

History: Fluorescence to the Rescue (1941-1945)

A desperate call to scientists and doctors:

find a treatment for malaria!

The origins of the SPF lie in the antimalarial research of the 1940s. During World War II, the United States government issued a desperate call to scientists and doctors: find a treatment for malaria! Since Japan had taken over most of the world's supply of quinine-the best known treatment-Allied forces in the Pacific Theater needed a new drug, and fast.

Led by Dr. James Shannon, scientists at Goldwater Memorial Hospital in New York City and elsewhere tested thousands of drugs during the war. In many of the tests, doctors gave their subjects malarial fever, then injected the patients with a particular drug. They needed to make sure the drug reached the malarial parasites in the blood and learn how to adjust the dosages to avoid nasty side effects.

The National Heart Institute Laboratory chiefs in the 1960s includes several members of the Goldwater group who worked with Dr. James A. Shannon

The problem was that some candidate drugs did not fluoresce at the specific wavelengths available to them with their fluorometer, and therefore these drugs were undetectable in the plasma. The doctors could not use fluorescence as a way of "seeing," or measuring, these drugs in the body. There had been reports of fluorescence at other wavelengths, but at the time there were no commercially available sensitive UV fluorometers. Though they did come up with a treatment for malaria, the Goldwater scientists realized that their ideas reached beyond their tools. They needed a new type of instrument.

With an instrument called a fluorometer, they could measure how much of the drug was in a patient's plasma sample.

The Coleman filter fluorometer

The Move to the NIH (1949)

In 1949 Dr. James Shannon, leader of the antimalarial research effort at Goldwater, was named director of the laboratories and clinics of the newly created National Heart Institute (NHI) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Bethesda, Maryland. He recruited researchers from Goldwater, including lab technician Julius Axelrod and Drs. Bernard Brodie, Sidney Udenfriend, Robert Berliner, and Robert Bowman. Because of their interest in fluorescence in medicine that originated with antimalarial drug research, one of the group's early projects was the development of a new instrument that could help them learn more about how fluorescence could be utilized in scientific research.

Dr. Robert Bowman of the Laboratory of Technical Development took the lead on the project in the early 1950s.

He was known for his talent in instrument-making, an indispensable skill in a research environment where scientists need good tools with which to test their theories and to lead them to new ideas.

The Laboratory of Technical Development at the National Heart Institute, early 1950s

Front row, left to right: Johnnie B. Langer, Hillary V. Trantham, Dr. Bert R. Boone, Robert E. Gorman, Patricia A. Caulfield. Back row, left to right: Dr. Harold J. Morowitz, Dr. Robert L. Bowman, Norman M. Garrahan, Dr. John L. Stephenson, Frank W. Noble.

Anything Glows (1950-1955)

NHI scientists did not yet know at which wavelengths many biological compounds would fluoresce. If the new instrument could emit light at wavelengths throughout the ultraviolet range, scientists might be able to excite fluorescence in compounds that could have interesting research applications. The question was, if they learned more about fluorescence, would this be useful in a practical as well as theoretical sense?

Working with others at NHI, Dr. Bowman developed the first prototype of his spectrophotofluorometer in 1955. Unlike previous fluorometers, this new instrument was able to vary the wavelength of exciting light as well as measure the intensity and wavelength of the emitted fluorescent light. This instrument could be used to survey biological compounds and help scientists figure out new ways to use fluorescence to study the body.

If they learned more about fluorescence, would this be useful in a practical as well as theoretical sense?

SPF project description sheet

NIH project description sheet for the"development of Spectrophotofluorometry and its application to biological measurements," 1955

AMINCO Steps In

Dr. Bowman had to improvise with his design. Authorized only to buy one expensive monochromator, for example, he built the other one from parts he obtained from his contacts in the New York junk shop trade. One of his parts, a Steinheil quartz prism spectrograph, had been "liberated" from Germany during the war. He made his first prototype SPF with a mixture of used and new parts, including diffraction gratings and mirrors attached to a stone benchtop and "glued" in place with wax."

Because of exciting results with the prototype, the American Instrument Company (AMINCO) of nearby Silver Spring, Maryland, became interested in marketing the new instrument. The company assigned an engineer, Hugh Howerton, to collaborate with Dr. Bowman on a commercial version of the SPF-one that could be made without wax and war relics. The first AMINCO-Bowman SPF was exhibited at the 1956 Pittsburgh Analytical Instrument Conference.

In order to build interest in its product and promote research in the field of fluorescence, AMINCO funded a postdoctoral fellowship in fluorescence analysis for research at the National Heart Institute. The first AMINCO fellow, Dr. Daniel Duggan, studied hundreds of fluorescent compounds. His research convinced Dr. Bowman and AMINCO that they should proceed with the production of the SPF.

He made his first prototype SPF with a mixture of used and new parts.

AMINCO engineer Hugh Howerton presenting a symposium about the SPF. Dr. Bowman is seated in the front row

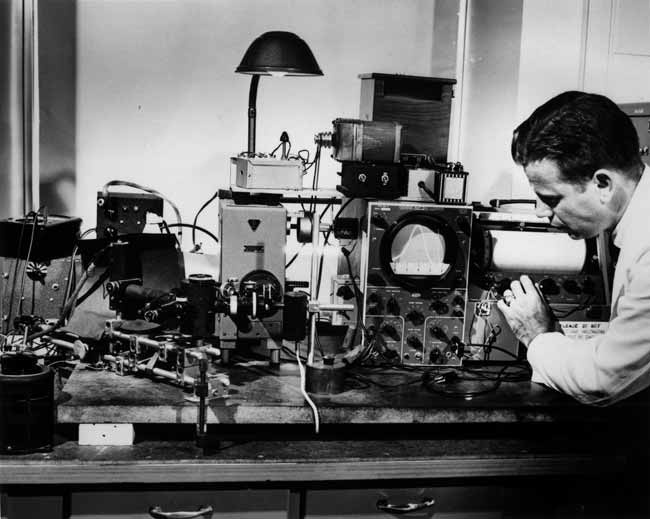

Dr. Daniel Duggan, a postdoctoral fellow at NHI, with the first laboratory prototype of the SPF

In the 1950s and 1960s, AMINCO marketed the SPF to the research field. Company sales representatives traveled across the country to train university faculty and other scientists how to use the instrument. The company even launched a newsletter called Fluorescence News.

AMINCO sold out its initial run of twenty-five instruments, an impressive record in the tiny biomedical research market.

This Aminco sales bulletin from 1956 advertised "A New Analytical Instrument." Click on image to flip through the pages of the bulletin

Aminco showcased new features of the SPF in this 1971 sales catalog. Click on image to flip through the pages of the catalog