Yellow Fever

Yellow fever had been around since at least the 18th century and was known and dreaded throughout the 19th century, especially in port towns with the arrival of new ships. It was endemic in Cuba, and so after the Spanish-American War, a Yellow Fever Commission was established in the United States to investigate. Walter Reed was the head of the commission, which established that mosquitoes transmitted the disease. The focus shifted to prevention via mosquito control.

At the same time, a “French strain” was discovered in Dakar, Senegal. Andrew Watson Sellards from Harvard and his team discovered the virus survived freezing, allowing transport of infected liver tissue. There were some crude vaccines using formalin and phenol-preserved liver tissue but with uncertain results. Max Theiler knew they needed a better host, so he then inoculated mice intracerebrally and found that the virus grew well. He created the first attenuated strain of yellow fever but with increased neurotropism.

The Rockefeller Foundation was involved in research in West Africa. Tragically, many of the lead researchers died of yellow fever from the 1925 expedition, but they were able to infect rhesus monkeys and therefore could remove the virus to the lab and study it. They discovered that serum from immune humans protected monkeys against infection, immune serum from South America protected against the African virus, and the killed virus would not confer immunity.

In 1932, new technique of cultivating the virus in embryonated eggs and freeze drying them came into use. The 17D virus strain from a chance mutation at the Rockefeller Institute was attenuated enough that it didn’t need protective immune serum. Trials continued in South America, but there were problems with encephalitis and jaundice.

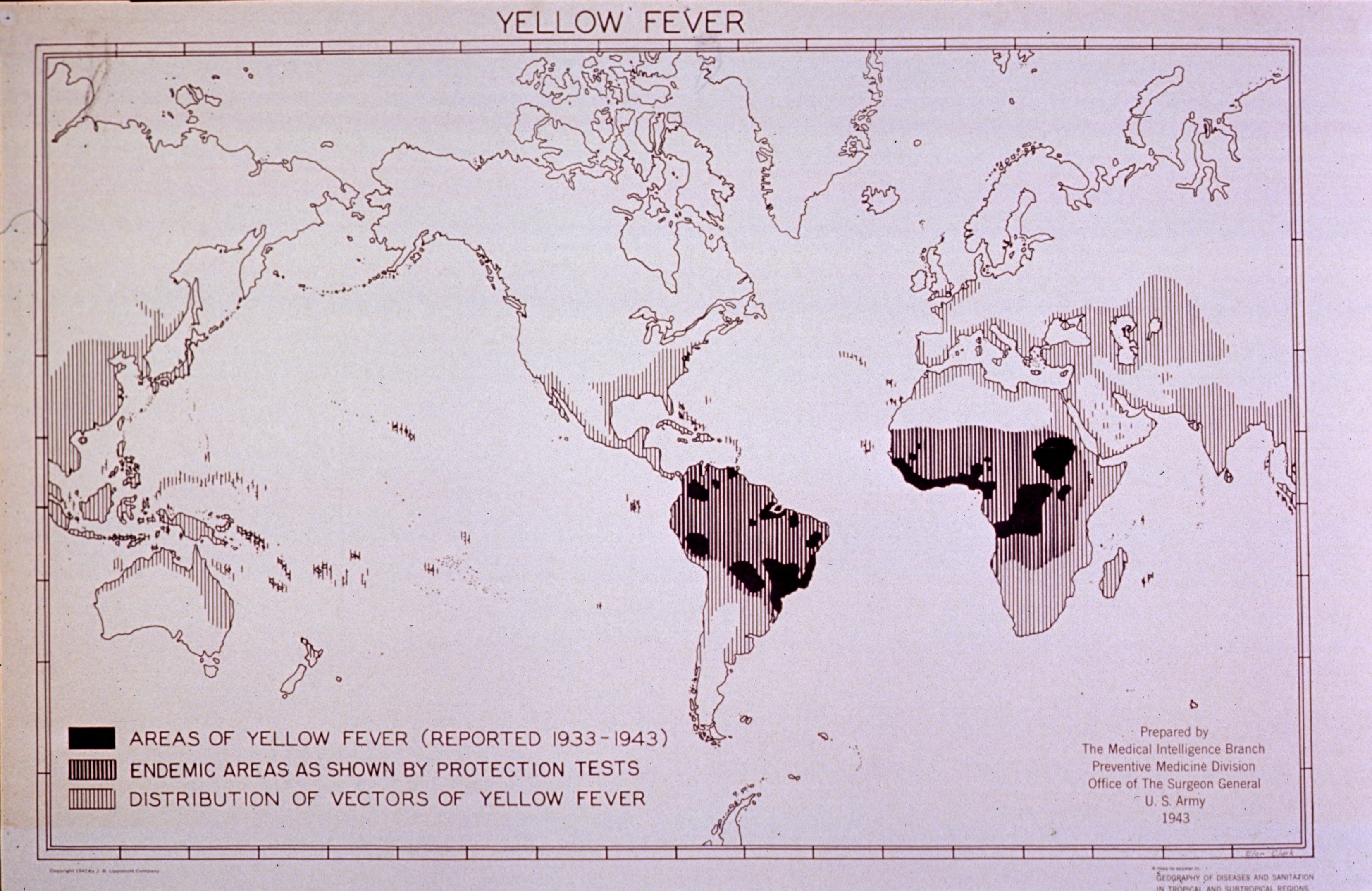

1943 Map of Yellow Fever from the U.S. Army National Library of Medicine

The yellow fever vaccine was first licensed in 1938. At the National Institutes of Health (NIH) from 1943 until her retirement in 1971, Dr. Margaret Pittman worked to assess the efficacy of and establish national and international standards for the production of the yellow fever vaccine. The NIH was also working on a yellow fever vaccine, like the Rockefeller Institute.

After WWII, the French and 17D vaccines widely used. By 1982 the French vaccine was discontinued. Since 1982, developments have included greater stabilization of the vaccine, with a longer storage life. In 1985, the complete genome of the yellow fever virus was published, allowing new research. Today all the vaccines are derived from two sub-strains of 17D.