Rocky Mountain Laboratories:

Canyon Creek Schoolhouse Laboratory

100th Anniversary

The brick schoolhouse in Canyon Creek, Montana, on a snowy day after it had become an official field station of the U.S. Public Health Service, circa 1921. Image: Office of NIH History and Stetten Museum, 1006

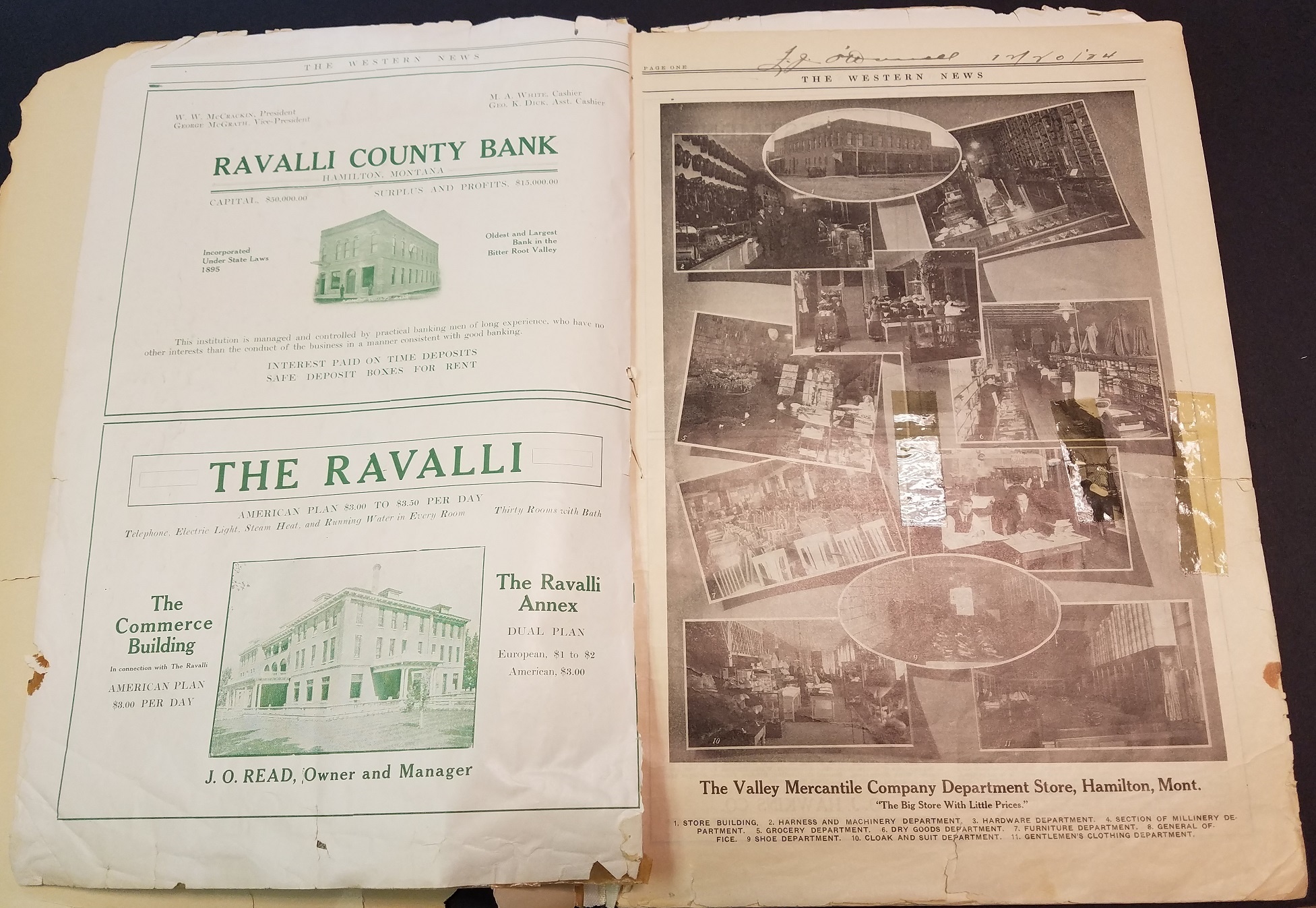

The Canyon Creek Schoolhouse was located in the Bitterroot Valley of Montana, an up-and-coming agricultural and business area in the early 1900s. In May 1910, the Western News printed a 27-page supplement called the “Bitter Root Valley Illustrated” describing the valley’s businesses, orchards and farmland, industry, and civic and religious life. What the supplement didn’t mention was that a highly fatal disease killed some residents every spring—and there was no prevention or treatment for it. The disease was Rocky Mountain spotted fever.

Dr. Frank J. O'Donnell wrote his name and the date "Dec. 20, 1924" on one of the pages of the Bitter Root Valley Illustrated supplement. He was a field agent for the Montana State Board of Entomology and did control work for the prevention of Rocky Mountain spotted fever and other tick-borne diseases endemic to the valley. We don’t know why he signed his name 14 years after the supplement had been published, but two notable things happened in his life that year: He helped begin production of Rocky Mountain spotted fever vaccine, enabling the promise of the Bitter Root Valley supplement to come true; and he went from being a Montana state employee to a U.S. Public Health Service staff member. Note that “Bitterroot” is today’s preferred spelling. Object: Office of NIH History and Stetten Museum, 18.10.1

Early residents of the Bitterroot Valley called the disease “black measles”, “blue disease”, “black typhus”, or just “fever.” This disease appeared in the valley after the slope had been cleared of trees for timber to make railway ties for the Northern Pacific Railroad, leaving the perfect environment for ticks. In 1902, the state of Montana asked scientists to investigate the mysterious disease. In less than 22 years, researchers identified what caused the disease, how it was transmitted to humans, and created a life-saving vaccine. This was nearly a miracle in an age with little knowledge of virology and only basic technology.

This drawing shows the spotted fever rash on a leg. It was drawn in 1903 by Dr. John F. Anderson when he became one of the first scientists to investigate Rocky Mountain spotted fever in Montana. Anderson was a U.S. Public Health Service officer assigned to the Hygienic Laboratory, which later became the National Institutes of Health.

Read his report. (20 MB)

Image: Office of NIH History and Stetten Museum, 1533-1

Encased in this key chain and pendant are Dermacentor andersoni ticks, the first species identified as transmitting Rocky Mountain spotted fever. This might strike us as an odd thing to do with ticks, but these trinkets symbolize the diseases carried by insects that the scientists of the Canyon Creek Schoolhouse would go on to research, including typhus, tularemia, mosquito-borne encephalitis, and plague as well as Rocky Mountain spotted fever.

This keychain and pendant belonged to Dr. Ralph R. Parker, who played a major role in Rocky Mountain spotted fever research, and who was director of the Rocky Mountain Laboratories in Hamilton, Montana, from 1927 to 1949. Object: Office of NIH History and Stetten Museum, 98.2.1-2

Today the Rocky Mountain Laboratories inhabit an entire campus where scientists conduct basic research on Lyme disease, prion diseases, antibiotic-resistant bacteria, Ebola, and coronavirus diseases like SARS, MERS, and COVID-19. We’ve come a long way in the 100 years since the Canyon Creek Schoolhouse became a laboratory to study Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Visit more of this online history to learn about the people and their work at the schoolhouse laboratory.

The Rocky Mountain Laboratories campus is snuggled in the valley below Downy Mountain in 2017. Image: Rocky Mountain Laboratories