HIV/AIDS

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) is a virus that attacks the body’s immune system. If HIV is not treated, it can lead to Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS). There is currently no cure for HIV, but with proper medical care, it can be controlled, and people can still live long, healthy lives.

HIV infections came from chimpanzees in Central Africa. The chimpanzee version of the virus (called simian immunodeficiency virus, or SIV) was probably passed to humans when humans hunted these chimpanzees for meat and came into contact with their infected blood. Studies show that HIV may have jumped from chimpanzees to humans as far back as the late 1800s. Over the decades, HIV slowly spread across Africa and into other parts of the world. The virus has existed in the United States since at least the mid-to-late-1970s.

Symptoms of HIV include fever, chills, rash, night sweats, muscle aches, sore throat, fatigue, swollen lymph nodes, and mouth ulcers. AIDS is the most severe phase of an HIV infection. People receive an AIDS diagnosis when their CD4 cell count drops below 200 cells/mm or if they develop certain opportunistic infections. People with AIDS have significantly damaged immune systems, making them susceptible to many severe illnesses, called opportunistic infections. Without treatment, people with AIDS typically survive about three years.

Dr. Robert C. Gallo of the National Cancer Institute. Gallo is a biomedical researcher and known for his research on the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and continues to work on HIV/AIDS research. Office of NIH History & Stetten Museum

Additionally, early biologics research on AIDS was carried out in Building 29A in the Division of Virology. The individuals involved in this early research include Drs. Lewellys F. Barker, Gerald V. Quinnan, Jr., Kathryn Zoon, and Jay Epstein.

Dr. H. Clifford Lane (left), one of the first investigators to study immunopathogenic mechanisms of HIV disease, and Dr. Anthony Fauci (right), who has made influential contributions to the understanding of how HIV destroys the body's defenses leading to the progression to AIDS. Office of NIH History & Stetten Museum

Drs. Thomas Folks and Guide Poli in their laboratory for AIDS research at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). Office of NIH History & Stetten Museum

As the clinical trials involving IL-2 progressed through 1983, OBRR continued its collaborations on other lymphokines in AIDS patients. For example, lymphoblastoid interferon yielded some benefit in Kaposi’s sarcoma, a systemic cancer primarily affecting those with AIDS, but has done little to alter the immunodeficiency or the course of the virus. Gamma interferon fared likewise. Preliminary results with IL-2 revealed some effect on immunity.

Assessing the impact of the epidemic on the blood supply and how to mitigate risk was the subject of many workshops and meetings that the Office participated in with the Departmental Task Force, industry, patient groups such as the National Hemophilia Foundation and the National Gay Task Force, blood collection organizations such as the American Association of Blood Banks and the American Red Cross, academe, the agency’s Blood Products Advisory Committee, and others.

FDA approved the first HIV test kit in March 1985 FDA History Office

OBRR licensed the Western Blot test to screen blood and validate previous tests for antibodies to the AIDS virus on 30 April 1987. This approval provides increased accuracy in testing blood. A combination test the detected antibodies to both HIV-1 and the much less common AIDS virus, HIV-2, was licensed in 1991. CBER had licensed a test for the latter virus the prior year, but many blood banks did not test for that virus given its very low frequency. FDA believed a combination test would be embraced more widely and lessen the risk of HIV transmission through the blood supply.

In 1988, CBER licensed a rapid screening test for AIDS that can be done without sophisticated equipment. Employing genetically engineered proteins and microscopic latex beads, the latex agglutination test could be performed in five minutes. However, this was not intended to replace tests used by blood banks and clinics, but it was expected to serve as a preliminary test where the results could be interpreted by a medical professional.

Also in 1988, CBER licensed alpha interferon for the treatment of Kaposi’s sarcoma. Multiple studies at NIAID and elsewhere indicated that up to about 50 percent of the patients in earlier stages of AIDS saw significant reduction of tumor sizes with high doses of interferon.

FDA Commissioner Dr. David Kessler, at left, with Associate Commissioner Sharon Holston at the 1992 groundbreaking ceremony for Building 29B, an AIDS research facility. FDA History Office

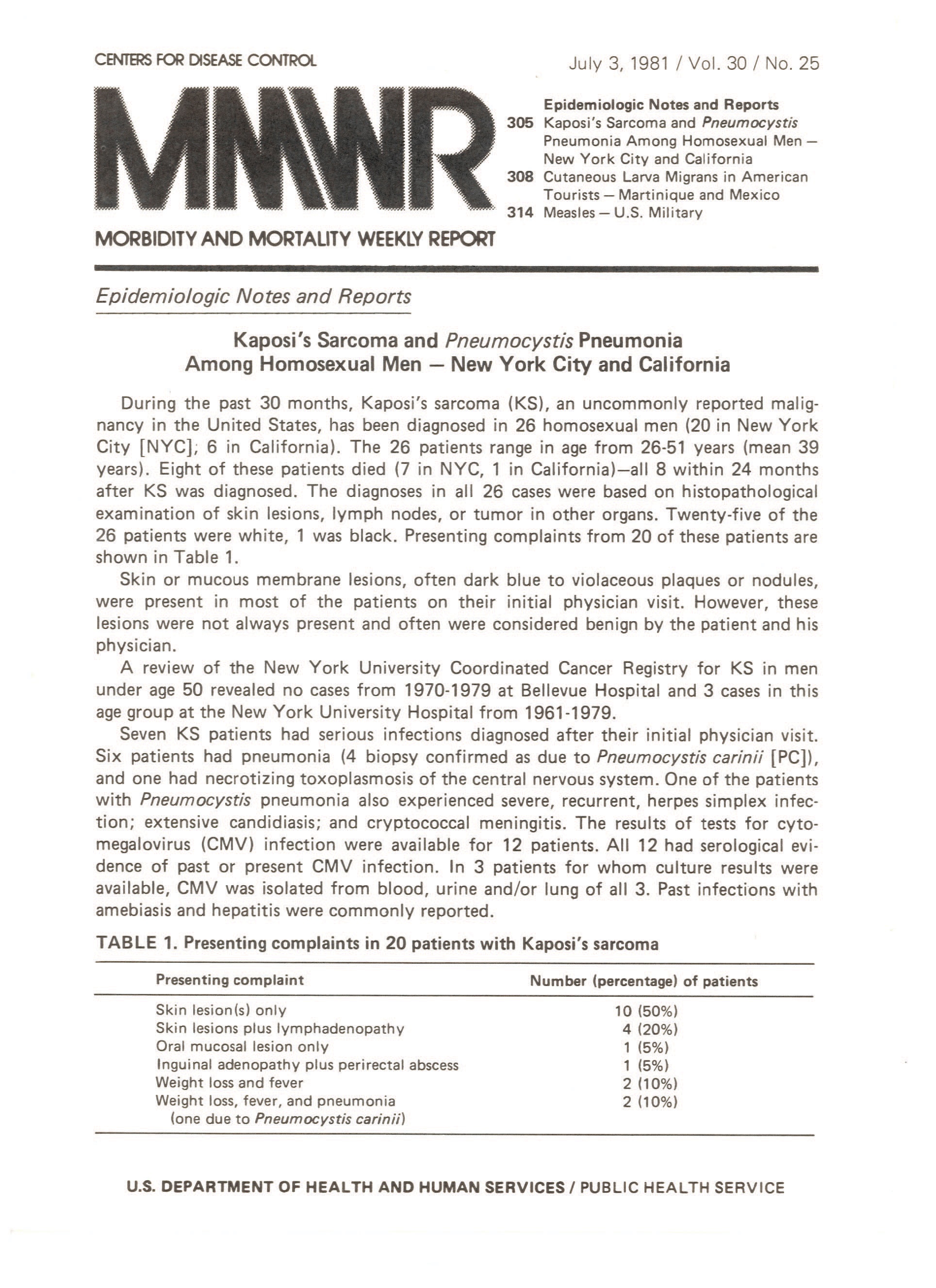

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (M.M.W.R.)

The following is text from one page of this document.

July 3, 1981 / Vol . 30 / No. 25

Epidemiologic Notes and Reports Table of Contents

- 305 Kaposi's Sarcoma and Pneumocystis Pneumonia Among Homosexual Men - New York City and California

- 308 Cutaneous Larva Migrans in American Tourists - Martinique and Mexico

- 314 Measles - U.S. Military Kaposi's Sarcoma and Pneumocystis Pneumonia Among Homosexual Men - New York City and California

Epidemiologic Notes and Reports

During the past 30 months, Kaposi's sarcoma (KS), an uncommonly reported malignancy in the United States, has been diagnosed in 26 homosexual men (20 in New York City [NYC]; 6 in California). The 26 patients range in age from 26-51 years (mean 39 years) . Eight of these patients died (7 in NYC, 1 in California)-all 8 within 24 months after KS was diagnosed. The diagnoses in all 26 cases were based on histopathological examination of skin lesions, lymph nodes, or tumor in other organs. Twenty-five of the 26 patients were white, 1 was black. Presenting complaints from 20 of these patients are shown in Table 1.

Skin or mucous membrane lesions, often dark blue to violaceous plaques or nodules, were present in most of the patients on their initial physician visit. However, these lesions were not always present and often were considered benign by the patient and his physician.

A review of the New York University Coordinated Cancer Registry for KS in men under age 50 revealed no cases from 1970-1979 at Bellevue Hospital and 3 cases in this age group at the New York University Hospital from 1961-1979.

Seven KS patients had serious infections diagnosed after their initial physician visit. Six patients had pneumonia (4 biopsy confirmed as due to Pneumocystis carinii [PC]), and one had necrotizing toxoplasmosis of the central nervous system. One of the patients

with Pneumocystis pneumonia also experienced severe, recurrent, herpes simplex infection; extensive candidiasis; and cryptococcal meningitis. The results of tests for cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection were available for 12 patients. All 12 had serological evidence

of past or present CMV infection. In 3 patients for whom culture results were available, CMV was isolated from blood, urine and/or lung of all 3. Past infections with amebiasis and hepatitis were commonly reported.

TABLE 1.

Presenting complaints in 20 patients with Kaposi's sarcoma

Presenting complaint - Number (percentage) of patients

Skin lesion(s) only - 10 (50%)

Skin lesions plus lymphadenopathy - 4 (20%)

Oral mucosal lesion only - 1 (5%)

Inguinal adenopathy plus perirectal abscess - 1 (5%)

Weight loss and fever - 2 (10%)

Weight loss, fever, and pneumonia (one due to Pneumocystis carinii) - 2 (10%)

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES/ PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE

Scan of the cover of the CDC's Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report from July 31, 1981, where the main article in this issue, "Kaposi's Sarcoma and Pneumocystic Pneumonia Among Homosexual Men--New York City and California," was the second describing groups of people with similar deadly symptoms that began the AIDS crisis. Office of NIH History & Stetten Museum

More Information:

- Progress Against AIDS Timeline

- NIAID History of AIDS Research Timeline

- FDA History page on AIDS

- Office of NIH History & Stetten Museum’s In Their Own Words exhibition.