Oversight and Protection Against Problems in Blood Banking

Blood Banking History

In 1934, the first human blood product licenses were issued to two pharmaceutical houses for human immune globulin prepared by ammonium sulfate precipitation. After the development of cold ethanol fractionation procedures, additional new products were licensed including normal human plasma (1940), normal serum albumin (1941), and immune serum globulin (1943). The first license for interstate shipment of whole blood, and the first blood bank license was issued to the Philadelphia Blood Bank in 1946. Each of these pre-1944 products were re-licensed under Section 351 of the Public Health Services Act (1944) and was considered analogous to therapeutic serum.

Blood and Blood Products

Blood products can include blood, red blood cells, fresh/frozen plasma, platelets, plasma derivatives, albumen, immune globulins, clotting factor concentrates, things that are made by recombinant DNA technology, reagents that test for infectious disease or are used to type the blood, and even the blood bank software used to keep track of the donations. All of these were regulated by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Division of Biologics Standards (DBS) and later the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) when they were transferred to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Court Cases

In 1962, the DBS brought suit against John P. Calise and the Westchester Blood Bank for intentionally altering the expiration dates on whole blood so that the product dating would exceed the 21-day requirement. He pleaded guilty and was convicted in 1963 on three counts of misbranding, three counts of false labeling, two counts of shipping an unlicensed biological product, and one count of conspiracy. Calise was placed on probation for five years and forbidden to engage in the manufacture, distribution, or sale of any biological, plasma, or blood products. The case marked the first court confirmation that blood is a drug under the definition of the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. The case also marked the first litigation brought against a biologics manufacturer.

Sidney Steinschreiber, owner of Sidcaps Laboratories, used the expired human plasma provided by John Calise to manufacture dried plasma intended for export, employed an irradiation process that did not comply with DBS standards, and labeled his products with an invalid license number. He was found guilty and sentenced to three months in jail. FDA History Office

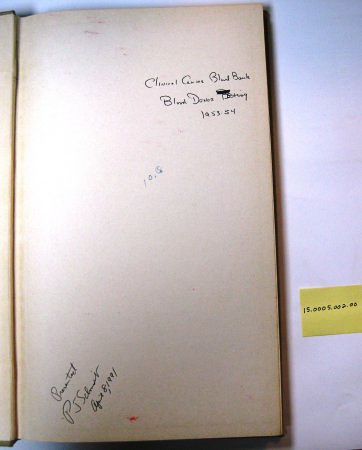

Blood banks and blood products were regulated through the NIH DBS Laboratory of Blood and Blood Products. In the 1950s, the NIH Blood Bank was part of the Laboratory of Blood and Blood Products. Much of the important research completed by the Laboratory was done hand in hand with the NIH Blood Bank. At some point in the late 1950s or early 1960s, the blood bank (which was located in the basement of the NIH Clinical Center) was administratively separated out from the Laboratory of Blood and Blood Products and became part of the Clinical Center (Department of Transfusion Medicine). When the DBS transitioned administratively from the NIH to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the Laboratory of Blood and Blood Products’ regulatory role continued in the Division of Blood and Blood Products.

Other court cases against blood banks soon followed:

- 1963 - Paterson, NJ blood bank had to surrender its Federal license after an outbreak of hepatitis from its donors.

- 1964 - Newark, NJ, the president of the Paterson Blood Bank, Inc. was charged for falsely labeling blood beyond the 21-day expiration and selling it to hospitals in NJ and NY. The blood bank was also convicted on 20 charges.

- 1968 - Dallas Blood Bank, Charles and Maxine Blank were charged with 27 violations of the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act, the Public Health Service Act, and two conspiracy statutes. They mislabeled units of whole blood and red blood cells, including changing the blood group, stating results of tests not completed, and extending the date on the blood. On an appeal., Maxine Bank’s conviction was reversed, and the Court of Appeals said that citrated whole blood and red blood cells were not products analogous to a therapeutic serum. Leaving a paradox where blood was considered a drug, but not a biologic. The amendment in 1970 to Section 351 took care of this by adding “blood, blood components and derivatives” to the act. This is the only direct evidence of a Congressional mandate for a Federal regulatory agency to license, inspect, and otherwise regulate blood banks.

FDA Research related to Blood and Blood Products

The FDA Bureau of Biologics research into cytomegaloviruses (CMV), beginning in 1973, aimed to promote further safety in the blood supply. The presence of CMV in those receiving large volume transfusions suggested that these might reside in the leukocytes of some donors. A recent study found that two out of 35 specimens of donor leukocytes had CMV. Though the Bureau had not yet confirmed this finding, routine testing for CMV could lessen risk in the blood supply.

In addition, the FDA Bureau of Biologics investigated the impact of phthalates leached from plastic bags used to store blood on human blood lymphocytes during the three-week storage period. No notable chromosomal damage was found, such that it could be concluded that phthalate did not produce a significant increase in chromosomally aberrant cells that could be transfused in humans.

In 1978, the Bureau of Biologics approved a preservative for whole blood and red blood cells that significantly lengthened the shelf life of these products. Previously, these could be stored for only up to 21 days, but the new preservative, citrate phosphate dextrose adenine (CDPA-1) extended that by more than two-thirds, to 35 days.

Three tests to detect HTLV-1, a retrovirus associated with both Adult T-cell Lymphoma and tropical spastic paraparesis received licenses in 1988. Since this virus appeared to be transmitted through the blood supply, these tests offered another valuable tool to blood collection and processing facilities to screen donated blood.