Interferon and Molecular Engineering

"Chris is unique because he thinks big. For example, when the rest of the scientific world was talking about how to conduct research with minute quantities of interferon, Chris said, ‘I'll synthesize it.’"

- —Dr. Gilbert Ashwell, NIH Record, July 21, 1981

Interferon: Can a Protein Be a Treatment?

| Span | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

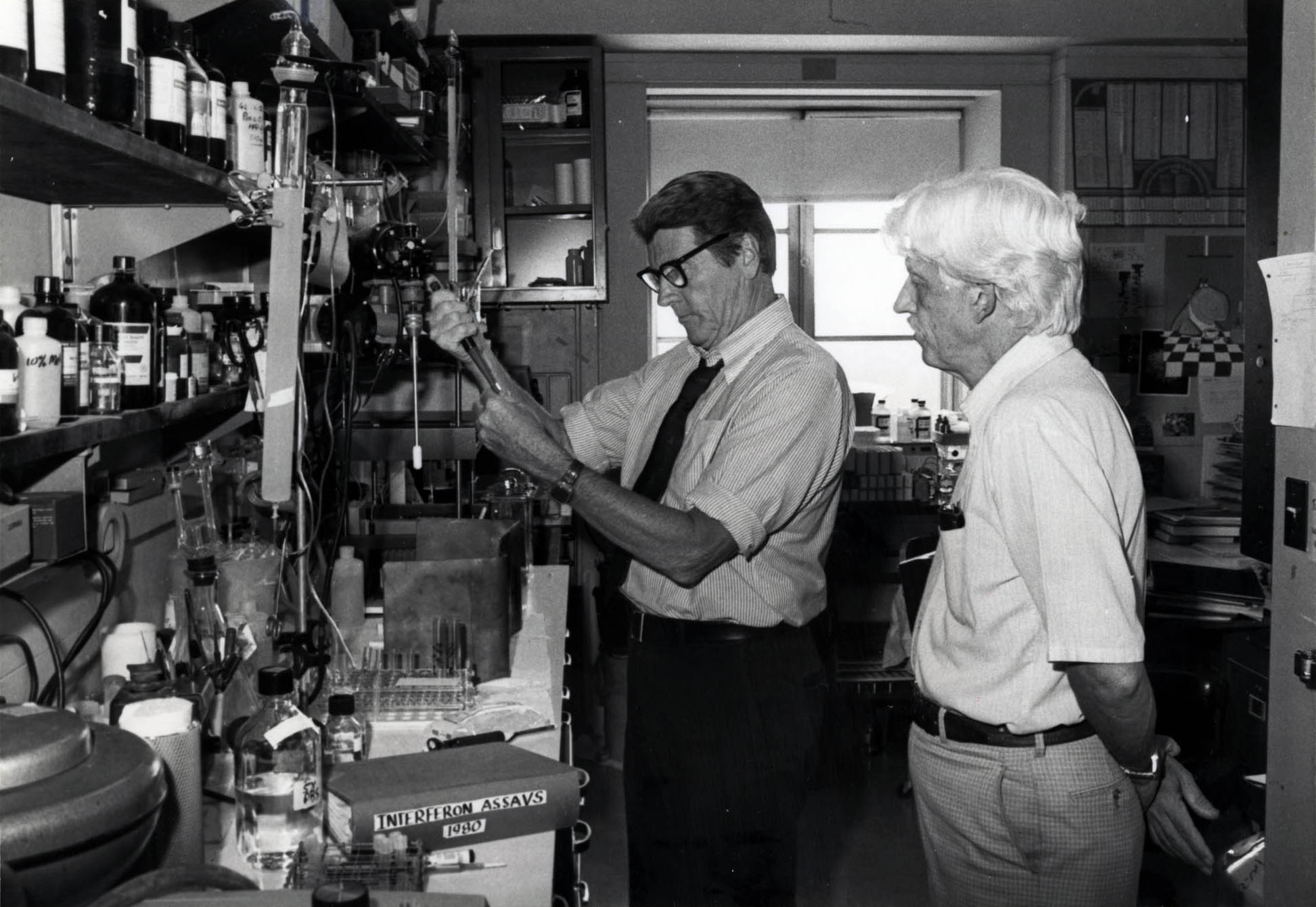

| A notebook “Interferon Assays” sits on the laboratory bench while Anfinsen speaks with Joseph “Ed” Rall, the Scientific Director of the National Institute of Arthritis and Metabolic Diseases, who himself was a major positive force on the NIH campus. Rall had recruited Anfinsen as chief of the Laboratory of Chemical Biology. |

| Span | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| National Library of Medicine |

| Dive | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|