The Molecular Basis of Evolution

"My pop wanted me to be an engineer, but science, which was second best, was as close as I could come…"

- —NIH Record, July 21, 1981

The Path to NIH

| Dive | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| Dive | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| Span | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Anfinsen during his fellowship at Carlsberg Laboratory in Copenhagen, Denmark, 1939-40. |

| Span | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| National Library of Medicine |

Anfinsen received his Ph.D. in biochemistry from Harvard University in 1943, where he became a faculty member after undertaking malaria research during World War II. While working with Arthur Solomon, Anfinsen perfected a technique he employed in his later work: using radioactive isotopes to examine the activity of amino acids.

Hugo Theorell's Laboratory

| Dive | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Early studies in the National Heart Institute

Anfinsen was recruited to the National Heart Institute (now the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute) at the NIH in 1950, a time when scientists were just beginning to explore the new fields of genetics and molecular biology, rooted in the classic discipline of chemistry. Here Anfinsen combined his research on the structure and function of proteins with investigations into cardiology-related areas such as lipids (fats).

| Span | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

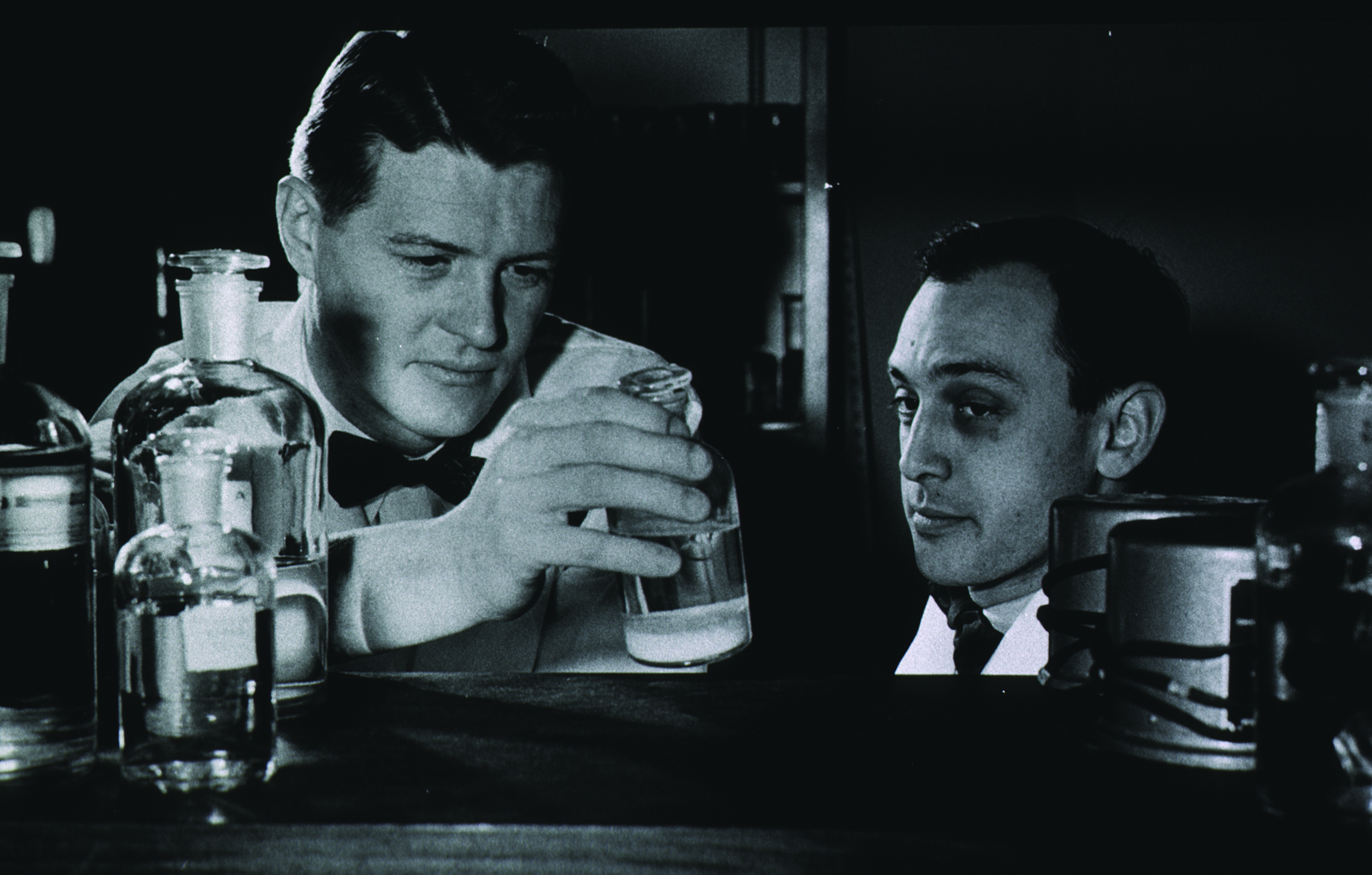

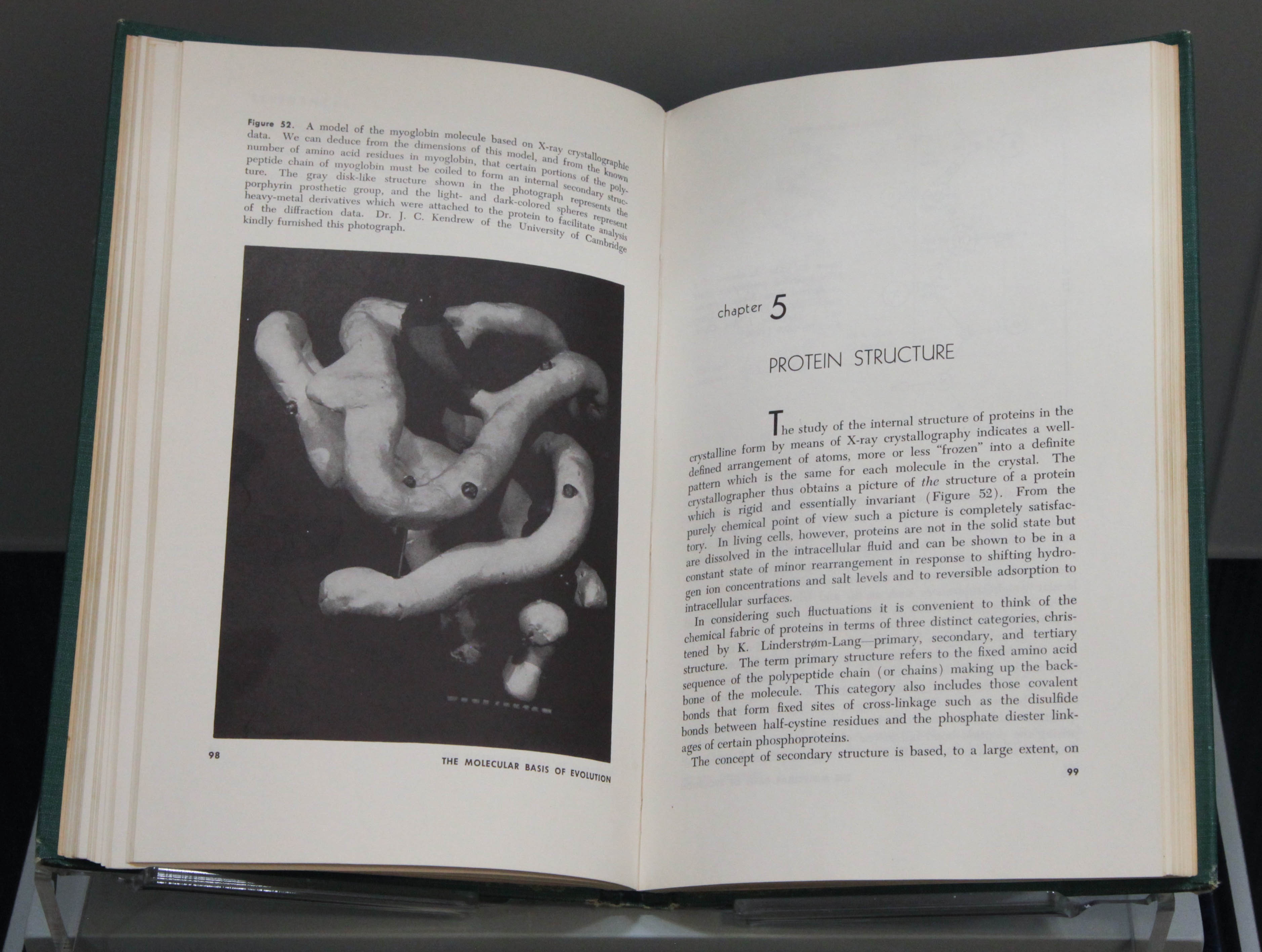

| This 1951 photo from the NIH Record highlighted studies by Anfinsen and Daniel Steinberg on the mechanism of protein synthesis. During the first decade at NIH, Anfinsen conducted research on cholesterol and lipoprotein metabolism as related to atherosclerosis, as well as on protein structure that included isolating enzymes and separating proteins into their constituent amino acids. These early protein studies were stepping stones to analyzing the stability of the three-dimensional protein structure and protein “folding” in the later 1950s and early 1960s for which he is best known today. |

| Span | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| PHOTO CREDIT: U.S. NATIONAL LIBRARY OF MEDICINE |

Anfinsen's Manifesto

| Dive | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||

|

| Span | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

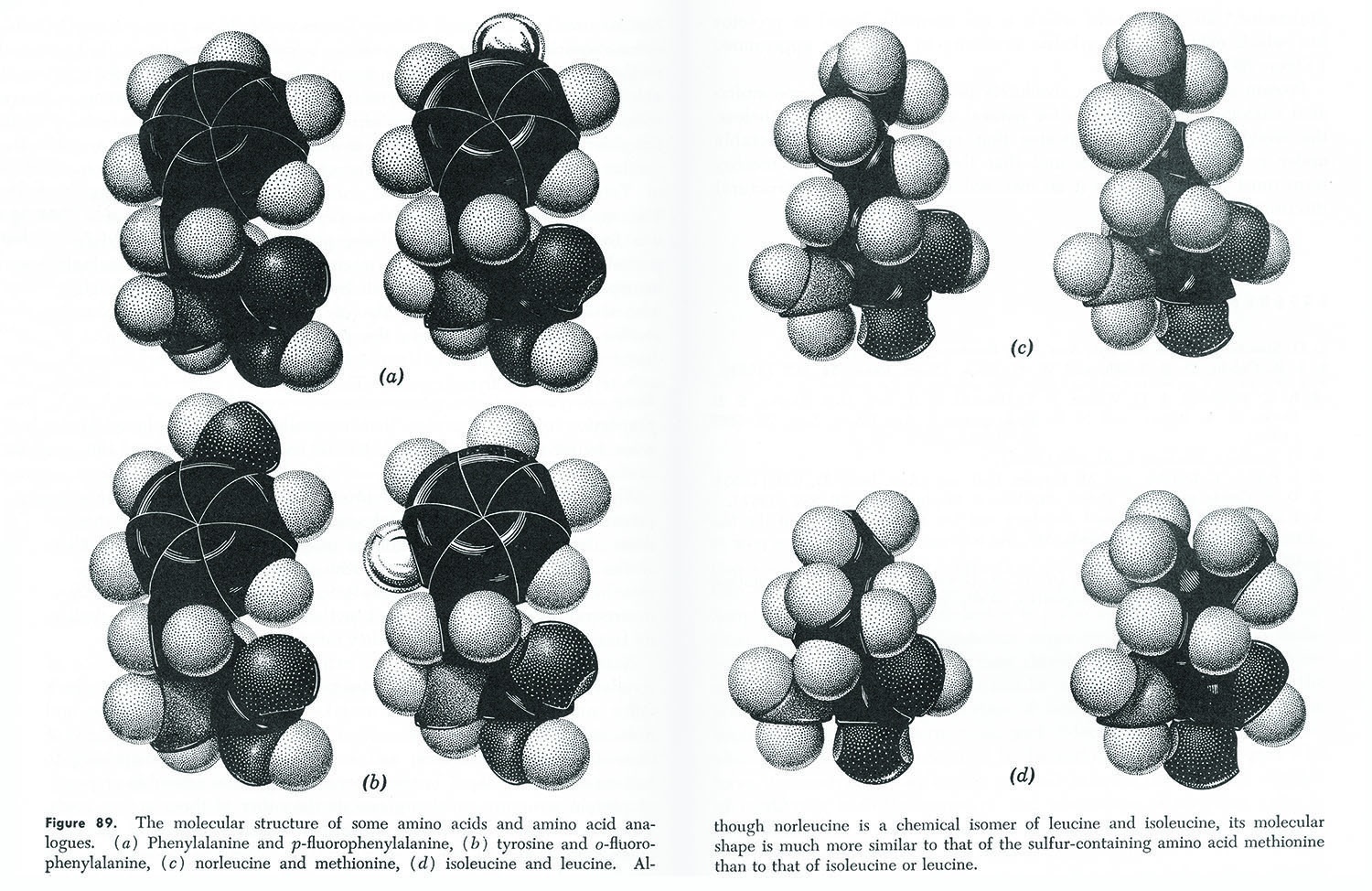

| These molecule structures of amino acids are featured in Anfinsen’s The Molecular Basis of Evolution. |

“The principal aim of this book has been to examine the basic principles underlying another possible method for the study of evolution [instead of fossils or comparative anatomy]. This method is based on the hypothesis that the individual proteins which characterize a particular species are unique reflections of the genes which control their synthesis. …[T]he structure of proteins may be a relatively direct expression of gene structure and …comparative protein chemistry may furnish a qualitative view of genotypic differences and similarities.”

The key to discovery? In a way, yes. This key was to the glass case displaying the staff directory for Building 3, which included an impressive array of scientists who served as Anfinsen's peers and collaborators, including future Nobel laureates Julius Axelrod and Arthur Kornberg, as well as later National Academy members Robert Berliner, Bernard Brodie, Donald Fredrickson, Edward Korn, and Earl and Thressa Stadtman.

Learn more about the scientists in Building 3.

| Button | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|