...

Bloom: The 1980s and the 1990s were times when the fields of molecular virology, molecular biology and structural biology were really taking off. I was able to use molecular cloning, DNA, the old style M13 sequencing, cloning and sequencing to do some really cool studies on Aleutian disease. I jokingly say, "I became the world's leader in that field," but it was probably true because I was the only one working in that field. I had a couple of talented postdoctoral fellows who came from Denmark. One was Søren Alexandersen [Dr. Søren Alexandersen], who recently was appointed the deputy director of the Danish State Serum Institute. I've stayed in touch with him. I characterized Aleutian disease as a parvovirus and then studied the pathogenesis of the infection. It was difficult to obtain viruses from infected mink tissue and get them to grow in culture. There was what we would now call a host restriction that prevented the pathogenic viruses from growing in culture. I tried to identify determinants of virulence and in vitro replication competence. We finally got to a point where we had done about as much as we could do. It was a challenging system to work with.

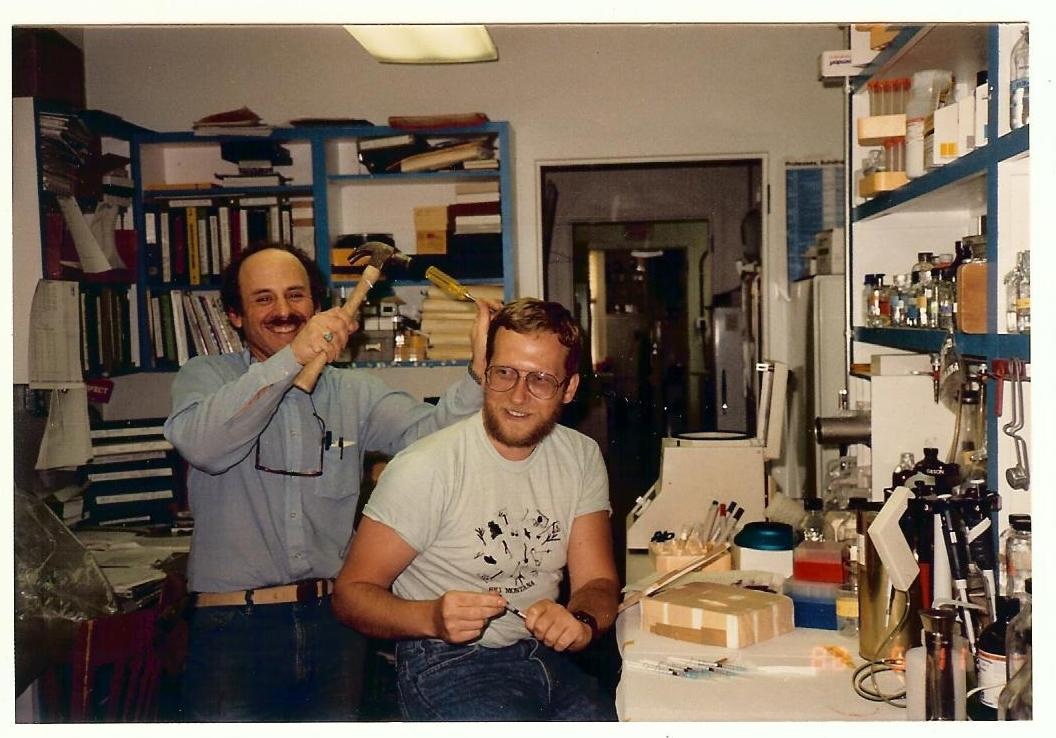

Marshall Bloom and Soren Alexandersen, ca 1987.

The interesting thing about the disease itself was really the in vivo system, the correlates of infection, and the persistent infection in the animal model. Unfortunately, as people are learning now with SARS-CoV-2, mink are a challenging animal model to work with. There are a limited number of cellular markers. The animals are not inbred. They only have kits once a year—the babies are called kits. So it's even harder than working with a ferret. Mink were challenging to work with. We ran up against roadblocks in trying to look at the in vivo pathogenesis aspects of the disease. Nevertheless, we did what I think is really top-notch work.

...

There are a lot of other people I haven't had a chance to mention who have been instrumental in my parvovirus work, primarily Kenneth Berns [Dr. Kenneth I. Berns], Neal Young [Dr. Neal S. Young], who's now with NHLBI [National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute], both good friends and good collaborators.

Laboratory of Persistent Viral Diseases group photo, 1987-1988.

Harden: I want to stop here for a moment. In the 2000s, you shift gears in your research to flaviviruses, but I'd like to set that aside for a moment and ask you to discuss the impact on RML of the terrorist attacks of September 11th, 2001. Both the Bethesda campus and the RML campus of NIH were transformed. Fences went up, and new buildings were built, and new responsibilities were given to the agency. But let's start with the day of the attacks. Tell me how it was at RML and about communications in the days afterwards with NIAID Bethesda, and about RML’s interaction with the citizens of Hamilton.

...

Kathy Zoon [Dr. Kathryn C. Zoon] was the Director of DIR at that point. We decided that to create a new Laboratory of Virology and do a search to identify a Chief. There were two candidates, and we selected Dr. Feldmann, Heinz Feldmann, who had been on the peer review panel advising us as the project went along, as the laboratory chief. We assumed what's called “beneficial occupancy” in early 2008 and hired Heinz. Heinz came down from Winnipeg that year and assumed the position of Chief of the Laboratory of Virology. Kathy had made me Acting Laboratory Chief until Heinz arrived. When Heinz became Lab Chief, we got all the Select Agent approvals, other permits, and this and that. We actually started doing level-four work, I think, in September of 2009. In all sincerity and candor, I think this is the best BSL-4 program in the country. I want to make sure it is clear that in spite of the major role I had, I have never personally done research at BSL4.

Marshall Bloom with Anthony Fauci during IRF construction, June 2006.

Harden: You also joined with the directors of almost all other BSL-4 facilities in North America to define the processes to select, train, and evaluate scientists and support staff. And because the CDC published it, it would have been a very deliberate process.

...

A few years after that, Sonja competed for and was selected as a tenure track investigator in the Laboratory of Virology. I was delighted and Sonja was able to continue independently all the superb innate immune studies that she was doing with a post-doctoral fellow named Travis Taylor [Dr. R. Travis Taylor] and the exceptionally talented Shelly Robertson [Dr. Shelly J. Robertson]. In other words, when Sonja established her Section in the Laboratory of Virology, Shelly and Travis went with her. So, I had the opportunity to start looking at aspects of flavivirus infections that weren't related to the innate immune response.

Sonja Best and Marshall Bloom in the Integrated Research Facility atrium, March 2009.

Harden: In 2014, your section was renamed the Biology of Vector-Borne Viruses. Why did that happen?

...

The research part was really astounding. However, it's important to recognize that research is based on having a lot of “get ready, get set” behind it. The lights have to stay on, and packages have to be delivered. Media has to be made or purchased; equipment has to be bought. I am confident that the entire response of Rocky Mountain Labs was essential, not just the scientists, but the maintenance people, the admin and purchasing people, the bio safety people, and the Veterinary Branch. Our vet branch had to deal with all these different animals and dozens of animal protocols. All of those people deserve an immense amount of credit because without their successful work and dedication, the research would simply not have been. It would've foundered. It would've not have been possible. I had a role in helping the response at an institutional level, along with a number of other people, including Josh Kellar [Joshua A. Kellar], the other RML Associate Director, the people from the NIH Office of Research Facilities, our bio safety staff, our safety staff and Veterinary Branch. Everyone here should take great pride in the fact that RML was able to do such an outstanding job.

Group photo of the RML Coronavirus volunteers, June 2021.

Harden: On the public facing side, you were very much involved. The American public has been politically polarized over COVID-19. Talk to me about your interactions with the public during the pandemic.

...

And then, in January 2021, again using staff volunteer labor led by Lt Commander Megan Brose [Lt. CDR Megan Brose], we set up a COVID vaccination clinic. We delivered a total of 779 doses of vaccine, 325 first doses, 329 second doses, one third dose and 125 boosters. We got 79% of the Rocky Mountain Labs staff vaccinated. Among the scientific staff, that number is about as close to a hundred percent as you can get.

The RML COVID-19 testing and vaccination center, January 2020.

In January of 2020, our Emergency Management team led by Roger Laferriere [Roger R. Laferriere] set up an incident management team specifically for COVID-19 impacts. It was the first at the entire NIH because we got worried very early on, "Are we going to have enough N95 masks for the researchers? Are we going to have enough gloves? Are we going to have enough hypodermic needles and syringes and pipet tips?" That COVID 19 incident management team still meets today to deal with some of the ongoing impacts.

...

Bloom: Yes, it is. It's a parasitic infection. I didn't know anything about it until it was identified here in Montana in December of 1994 by Beth. Shortly thereafter, I was contacted by a friend, Pat Graham [Patrick J. Graham], who was the director of the Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks. He knew I studied infectious diseases. Pat had talked to Marc Racicot [Marc Racicot], who was the governor of Montana at the time. They asked me to put together and chair a task force of scientists, citizens, anglers, business people, and conservationists from around the state to try to learn more about whirling disease, what the impact was going to be in Montana, and what we should do about it. It's not very often that you get to use your job in your hobby. But as a person with some knowledge about infectious diseases, in 1995, Pat and I, along with others, put together a Montana whirling disease task force. I was able to recruit Stanley Falkow, Lucy Tompkins, as well as Dave Baltimore and Irv Weissman--all eminent scientists. Karl Johnson, the guy who discovered Ebola virus and who was a hardcore fly fisherman, was also on the task force. He's about 93 or 94 now, and that was actually where I really first got to know him well. We were asked to take a look at the situation and come up with recommendations about what to do. We also started the Whirling Disease Foundation to raise private money to underwrite the research studies that the Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks was not able to do.

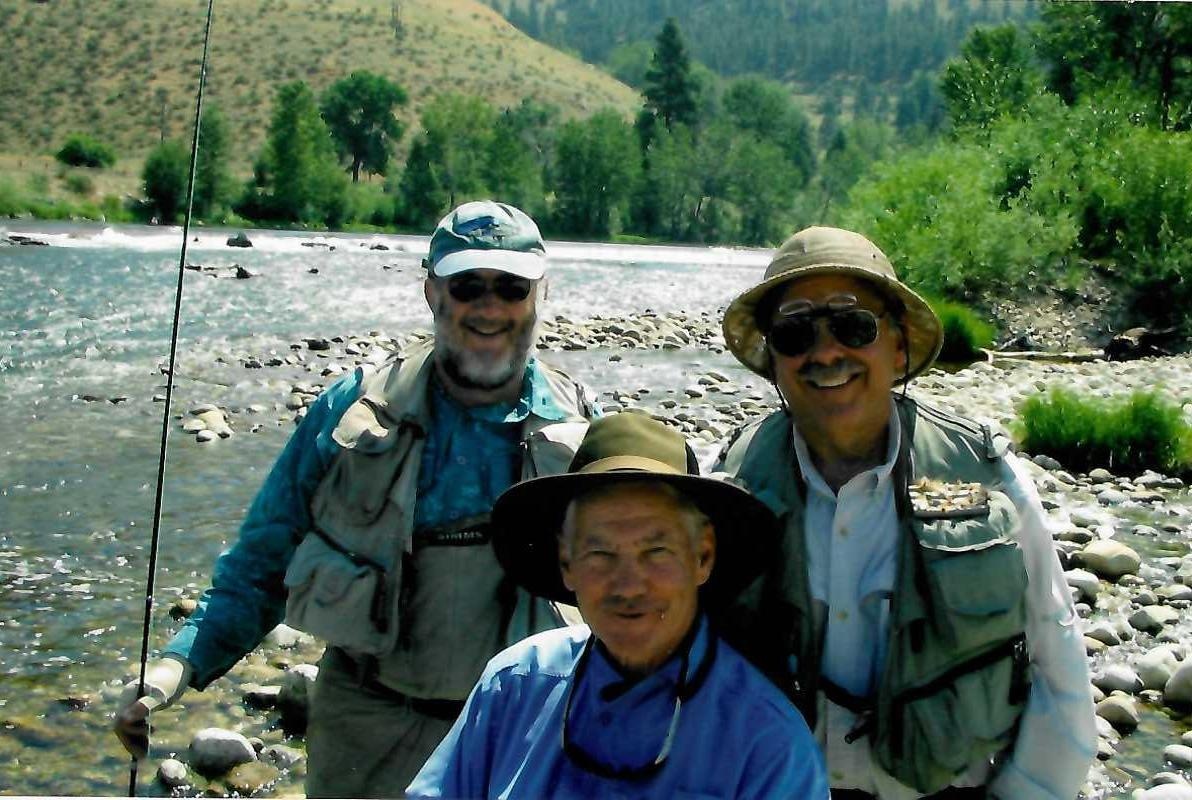

Irving Weissman, Stanley Falkow, and Marshall Bloom fishing.

We decided early on that there would be a three-fold approach: research, management, and education, and they were the three goals we published in both an interim report and our final report. I got an award from the governor as well an award from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for this effort. I feel it was really important that I and the other scientists were part this effort. The biologists at the Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks Department, trout conservationists and others worried that Montana was going to throw up its hands and say, "We're going to solve this problem by stocking fish out of hatcheries again." That would've been the end of the wild trout and the native trout in the state of Montana. But through our Whirling Disease Task Force, the tremendous support of Governor Racicot and other people in his administration, the advocacy of Trout Unlimited, and the network that we were able to build on this Whirling Disease Task Force, we were able to fight off the interests that wanted to solve the problem by stocking, which is what they've done in all the other states.

...