...

We also had a close relationship with my mom's parents, my maternal grandparents, George and Freda Bauslaugh. They lived just a few blocks away while we were growing up. My grandfather loved to fish, and he introduced my brother and me to fishing. We spent a lot of time fishing with him. My dad grew up in a broken household and was not able to go to college. At the age of 17 or 18, he became an electrician. He was also a professional musician. I think he would have loved to go to college, but he just couldn't do it with a single mom working very hard to keep a roof over their heads and food on the table.

| Span | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

Gone fishing with grandpa George. Left to right, Tom, Grandpa, brother Mark; 1958 |

.

My parents were terrific. There was no pressure as we grew up to go to college. My brother and I did pretty much what we wanted. We both did well in school, and my mom pushed us to join almost everything we could in elementary school and junior high.

...

When I graduated in '69, and was working on that project, Dr. Cogswell got a call from Dr. Frank Pitelka [Dr. Frank A. Pitelka] at Berkeley, who said, "We suddenly have money for a research assistant to help us up in Alaska, Northern Alaska near Point Barrow. Do you have anybody that we can hire?" Dr. Cogswell came to me and said, "Are you interested in going to Alaska? You have to leave in about five days." I said, "Well, let me talk to my wife about this." We discussed it, and both of us were fine with it. I viewed it as a great opportunity to go to the Arctic and work on the north slope and learn what it was like to work with a group of ecologists from Berkeley. So I did that, and it was a wonderful experience. It was tough work. The sun never set the whole time I was up there, as we were well above the Arctic Circle. That took a bit of adjustment. It is a fond memory; it was a great experience.

| Span | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

Tom Schwan, on the shore of Arctic Ocean, near Barrow (now Utqiagvik), Alaska, while working as field assistant on bird project; July 1969. |

I worked under a graduate student from Berkeley. That situation was informative and helpful for me because I was this fellow’s very first technical assistant in the field. He enjoyed the power. He enjoyed the authority he had over me. And there were times when I resented it even if overall it was a great experience. It was the beginning of many technical positions I held in which I was working for somebody else, and at some point down the road, I decided it might be better to call the shots myself than to do what somebody else was telling me to do. That helped me head towards becoming an independent investigator.

...

Harden: That's perhaps the most interesting Vietnam story I have heard among the many I have heard while doing many interviews! I am of that generation, so I have heard many stories about how young men got out of going to Vietnam, but yours may be the most straightforward and admirable for standing on principled opposition to the war and accepting the consequences.U.S. Peace Corps teacher training, Kapsabet, Kenya. Far left, Tom; August 1974.

Schwan: Here’s a follow up to the story. After serving my sentence, I went into the Peace Corps and was sent to Kenya. While I was there, my folks sent me a package that allowed me to apply for a Presidential pardon from President Gerald Ford. And I really didn’t want a pardon. I had done everything they asked. I didn't go to Canada. I didn't refuse to report. I reported, I did my alternate service, went through my probation. I had completed everything that the government wanted for me to do as someone who opposed the war. I wrote back to my parents and I said, "I'm not going to do this. Ford just gave Nixon [President Richard Nixon] a pardon. I don't want a pardon from him."

...

Schwan: Yes, I was on my own. I learned subsequently who both of those reviewers were for my first paper, and they both came to respect me. They both have passed away now, but eventually, as I did more work, they realized I wasn't so lazy and as dumb as they accused me of being.

| Span | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

U.S. Peace Corps teacher training, Kapsabet, Kenya. Far left, Tom; August 1974. |

Harden: Let's go to Kenya from 1974 to '76, when you were a Peace Corps volunteer. Tell me about your assignments there and what you did in those years.

...

I was very fortunate at UC Berkeley. My thesis advisor was Dr. Deane Furman [Dr. Deane P. Furman], who was internationally known for his taxonomic work on mites. I turned out to be his last Ph.D. student. He was “hands off” with his students, so his students had to be very independent. In all the years he taught at Berkeley and had graduate students who produced doctoral theses, he never once co-authored a paper with a student regarding his or her thesis work. He did his taxonomy, and his students did their projects. That just wouldn't happen today. But because he was so hands off, I was not very happy during my first year there. I had hoped that I would have a mentor and a supervisor who would take me under his or her wing and help me develop as a scientist. Although Dr. Furman was always there in his office when I had a question, and he was honest and straightforward and a gentleman, I really wanted more. Luckily just down the hall was the Professor named John R. Anderson [Dr. John R. Anderson]. He goes by “Andy.”

| Span | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

Mt. Palomar State Park, California, setting mouse trap for flea study; November 1981. |

Andy took me under his wing. He hired me on a mosquito project, and I helped on his project on dung beetles. If it weren't for Andy, I probably would have left Berkeley. Just like Dr. Edward Lyke, who turned things around for me at Cal State Hayward, Andy really made me want to stay at Berkeley and work with him. And so I helped him early on, studying tree hole mosquitoes. He was not my thesis advisor, but he was the chairman of my graduate committee and oversaw my written and oral exams. He and his wife Shereen would have me over to dinner. We worked in the field together and published several papers together. He made all the difference. Andy is 90 years old now and we still keep in contact with each other.

...

Schwan: My thesis advisor, Dr. Dean Furman, worked on a large monograph on the ticks of California while I was his student. That was his last big project. He actually went to the Rocky Mountain Laboratory on sabbatical, spent nine months here in Hamilton. And this was before the collection of ticks was moved to Silver Spring, Maryland. Because of this, I was well aware of the tick collection here at RML. I was also following the CDC’s [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports [MMWR] on Lyme disease and what could or could not be causing it. I helped Dr. Furman, preparing maps for his monograph on the ticks. We were very well aware of what was happening in Montana and concerned for sure.

| Span | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

Berkeley, California, ready to drive to New Haven, Connecticut to begin postdoctoral fellowship at Yale University. Behind me (left to right) are my father, Creighton, mother Beverly, and grandmother Freda; August 1983. |

Harden: When you finished Harden: When you finished at Berkeley, you went to the Yale Arbovirus Research Unit [YARU], which in 1964 had taken over from the Rockefeller Institute as the predominant national arbovirus research institution. Tell me about your work at Yale, what you studied and what you learned.

...

I arrived at Yale just before the cause of AIDS [acquired immune deficiency syndrome] had been discovered. Dr. Shope had me testing serum samples from a large population of gay men in Florida, to see if they had antibodies to certain mosquito-borne viruses that might link these mosquito-borne viruses to AIDS.

| Span | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

Mono Lake, California; ready to raft to an island to collect ticks for virus isolation at Yale University; January 1984. |

Although I helped on that project, my own work focused on ticks and viruses from Mono Lake, California. When I was at Berkeley, I had begun a project on the ticks on islands in Mono Lake, a highly saline lake in eastern California. I started that work in 1981 with the help of David Winkler [Dr. David W. Winkler], a zoology graduate student at the time. I went to Yale in 1983, and then I was able to focus on the biology of these ticks and the viruses that these ticks transmitted to the birds and possibly to humans. A lot of my work was based on working with the ticks from Mono lake in the laboratory—working out the life cycle, doing transmission studies of Mono Lake virus, which is the virus that these ticks transmit. And that really got me interested in tick-borne viruses.

At Yale, as I said, I learned a lot of techniques and laboratory skills, and it was exciting to be there. I enjoyed living in New Haven for three years, and all of the faculty were tremendous and so willing to help me. I was supported by an NIH Training Grant awarded to Dr. Francis Black [Dr. Francis L. Black], an international measles expert. He would funnel out training grants to different units, and I was able to be hired for the first two years on his NIH Training Grant given to the Yale Arbovirus Research Unit. Again, I worked primarily on tick-borne viruses from California. We also did field work in Newfoundland and isolated viruses from ticks we collected from seabird colonies there.

| Span | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

Holding an Atlantic Puffin, Great Island, Newfoundland, while collecting ticks from burrows for virus isolation at Yale University; July 1985. |

Harden: When you finished your postdoc in 1986, you came to RML. Were you aware of the upheaval that had been occurring as NIAID decided to phase out its historic focus on medical entomology and instead emphasize molecular biology?

...

When I first came on board, Alan Barbour [Dr. Alan G. Barbour] was still here, but he was basically packing up to move to San Antonio, Texas. Alan left in September/October of ’86, and I was given his laboratory space and his technicians, Merry and Bob. I even rented Alan’s house in Hamilton, and by the end of the year I bought his house. He and his wife Ann and two boys lived just a few blocks from the lab and this is where I lived for the next 22 years.

| Span | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

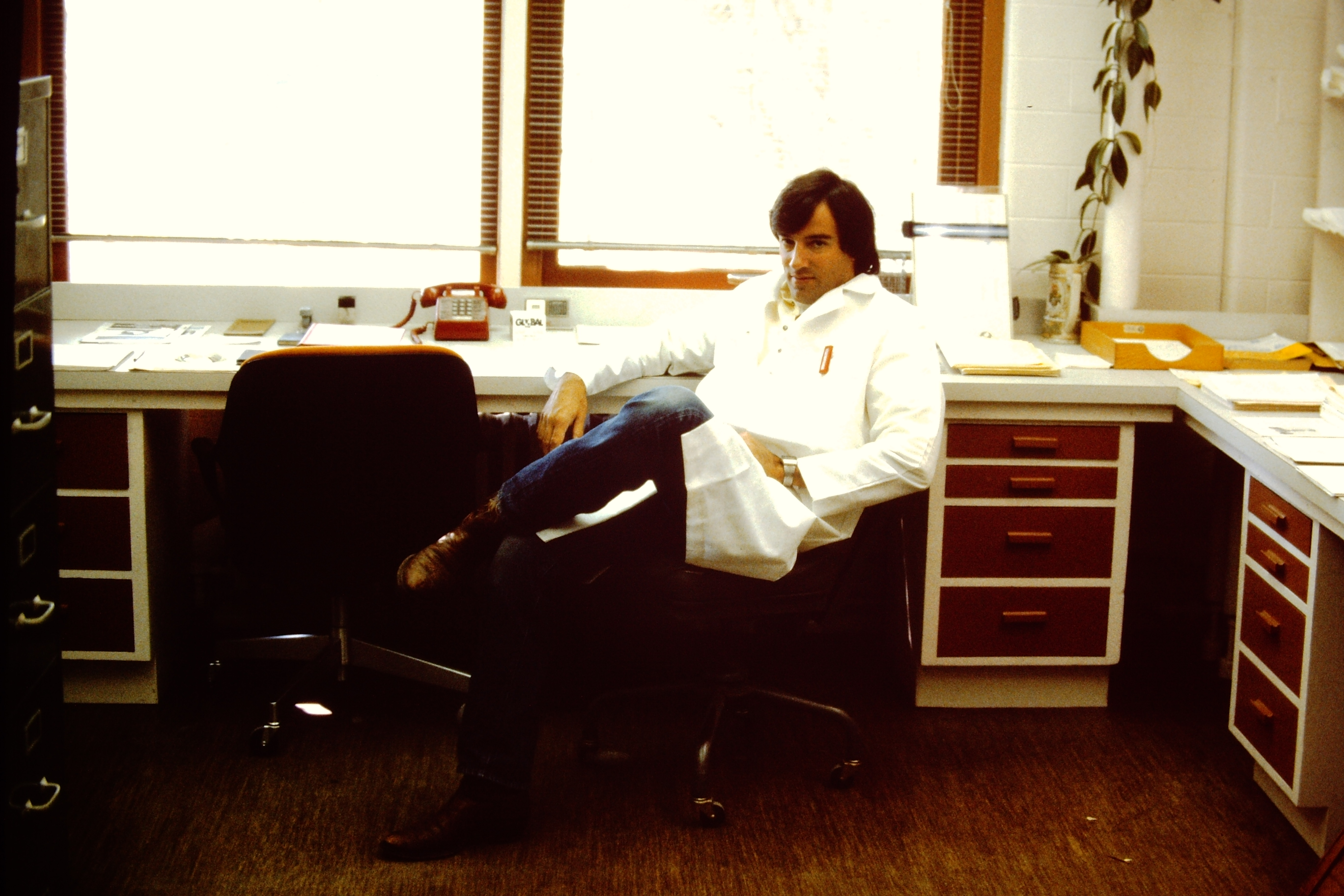

In my first office at RML; Spring 1987. |

When I started at RML, I may have made a mistake by wanting to work on too many things. I wanted to work on plague. I wanted to work on spotted fever. I wanted to work on Colorado tick fever virus. I wanted to do too much. But one of the things that I realized was that I was coming into a lab that knew how to work on Borrelia. The resources there to work on Lyme disease spirochetes were incredible. Both technicians who were going to work with me were highly skilled and had helped Alan Barbour with much of the early work on the Lyme disease spirochetes. And so when Alan left and Willy was there as Emeritus—although Willy had retired in January, he was still working at the lab as a Scientist Emeritus--Willy became my new mentor. He took me under his wing and helped me learn how to work with Borrelia. We collaborated on several projects for the first few years. It was wonderful working with him. He was great, so generous and helpful, and he cared about my career development. I was very fortunate.

Dr. Gallin was the Scientific Director at the time. Back then, and, in fact, the whole time I've been at RML, I experienced many administrative changes to the layout of RML, and the administrative units to which I belonged. It was bit of a rollercoaster over the years, and we can get into that if you want.

| Span | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

Dr. Willy Burgdorfer “playing” with me in the lab, RML; 1987. |

Harden: I do, but first, tell me about your research to detect the agent of Lyme disease using monoclonal antibodies and nucleic acid hybridization probes. This is the research that permits scientists to distinguish Lyme disease Borrelia from relapsing fever Borrelia. And if I'm reading your CV correctly, this work led to patents in the 1990s and to your 1993 Award of Merit for Excellence in Technology Transfer. Would you tell me about this work?

...

This work led to the patent application for a diagnostic antigen. Warren and I were the co-inventors. And of course the Institute held the patent. It took a while for that to happen, but it felt good to actually do something in the lab that got developed into a product that was being used to help in the serological diagnosis of Lyme disease.

| Span | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

Being presented with the Federal Laboratory Consortium Award for Technology Transfer for Lyme disease serological test. Left to right, Dr. Philip Chen, Dr. John Gallin, Tom, and MaryAnn Guerra; April 1993. |

HardenHarden: In the New York Times today there was an article about chronic pain and infection related to what some people call “chronic Lyme disease.” Other people say that there is no such thing as “chronic Lyme disease,” because no Borrelia burgdorferi organisms can be detected. Are you willing to comment on this controversy?

...

Schwan: I'll just say it's a really complex issue and because I am not trained in medicine and have never treated or cared for patients in this category, I don’t feel qualified to respond.

| Span | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

Ready to set a rodent trap for relapsing fever project, northern California; September 1990. |

Harden: In 1993 you were named the R. R. Parker Memorial Lecturer by INCDNCM, the International Conference on Diseases of Nature, Communicable to Humans. What surprised me was the topic on which you chose to speak. Instead of your work on Borrelia serology, you spoke on, "A Personal View of Fleas and Plague During the Last Two Decades." Why did you choose that topic?

...

Schwan: Yes, he was a wealth of knowledge, but once he got going, it was hard to stop him. l loved getting to know him, and I was the one that received in his name the 1991 Harry Hoogstraal Medal for Outstanding Achievement in Medical Entomology from the American Society for Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. I went to the meeting and brought the medal back to Hamilton for him since he was unable to attend. We did a ceremony at his home at which I gave him the medal, and there was a story about it published in the Ravalli Republic, our local newspaper.

| Span | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

Presenting Dr. William Jellison (right) with the Harry Hoogstraal Medical awarded by the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene; December 1991. |

Harden: That's nice. One more sideways question here about the tick collection. After Dr. Hoogstraal donated his collection to augment the RML collection, it was all moved to Georgia Southern University. Was there any commentary at RML about why it was moved and whether it mattered? I don't know that there was, I'm just curious.

...

Schwan: Jim Oliver [Dr. James H. Oliver, Jr.] wanted it there, and he was a major force in having that happen.

Harden: In In July , 1994, you married Carol Schwan [Carol Lynn Schwan] and adopted her younger son, Shawn [Shawn Fagan Schwan]. In your work life, you moved in late 1994 or early 1995 to the Laboratory of Microbial Structure and Function. Tell me about why you moved from the Vectors and Pathogens lab to the Microbial Structure and Function lab.

| Span | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

Laboratory of Vectors and Pathogens, RML. Tom (standing, fifth from left) between Dr. Willy Burgdorfer and Dr. Claude Garon (Laboratory Chief), fourth and sixth from left, respectively; October 1991. |

Schwan: That happened when Dr. Gallin reorganized the laboratories. What had been the Laboratory of Vectors and Pathogens, with Claude Garon as Chief and in which I was a Senior Staff Fellow, was disbanded. Claude became Chief of the Microscopy Branch, which was separate from the other laboratories. My group was reassigned to the Laboratory of Microbial Structure and Function, where John Swanson was Laboratory Chief.

| Span | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

After reassignment to the Laboratory of Microbial Structure and Function. Left to right, Dr. John Swanson (Laboratory Chief), Dr. Seth Pincus, Dr. Patricia Rosa, and Tom; 1994. |

Another group that had been in the Laboratory of Vectors and Pathogens was moved to Harlan Caldwell’s Laboratory of Intracellular Parasites. That group worked primarily on Campylobacter and another group stayed with Claude's Branch. Claude also had postdocs who continued to work on Borrelia, and Claude and his team of microscopists provided electron microscopy support for all the researchers at RML.

...

In 1999, Dr. Musser came onboard as Chief of the newly created Laboratory of Human Bacterial Pathogenesis, which replaced the Laboratory of Microbial Structure and Function. I became a PI in that new lab. So, at this point, I had had Claude, then John, and now Jim as my lab chief. Jim came on board, was strongly supported, and built a big program. He and his large group were very productive in the number of publications. Then one day in 2003, he came to my office and told me that he was leaving RML to return to Houston.

Harden: Whoa.

| Span | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

After reorganization and reassignment to the Laboratory of Human Bacterial Pathogenesis, RML. Left to right, Dr. Joe Hinnebusch, Dr. Frank DeLeo, Dr. Michael Otto, Dr. James Musser (Laboratory Chief), Dr. Patricia Rosa, Dr. Robert Belland, and Tom; 2000. |

Schwan: Suddenly, I once again became an Acting Chief. There I was again, trying to keep things going, keep the boat from sinking, and keep my own work going forward as best I could. But it was a bit more complicated this time as Jim, his new institution, and the DIR worked out an interagency agreement for Jim to continue to supervise all his folks at RML from Texas, with occasional visits to Hamilton.

...

Until I retired, I worked primarily on tick-borne relapsing fever. That became my passion and my focus. And it was during this time that Dr. Zoon and Dr. Barron [Dr. Karyl Barron], Deputy Director of NIAID, supported me in developing a relapsing fever project in Mali, in West Africa, at the research and training center outside Bamako. Dr. Zoon also was very supportive of my having a field project on relapsing fever in Montana. I really appreciated her support enabling my group and me to do some field work. It really saved me in a sense because I finally felt I was doing what I was hired to do back in the 1980s. I was finally able to bring together my interests and skills both in the field and what I had learned in the laboratory. And we accomplished some work I am very proud of.

| Span | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

Coming out of the attic to collect ticks in a cabin associated with an outbreak of tick-borne relapsing fever, Wild Horse Island, Flathead Lake, Montana; August 2002. |

We had great projects in Mali and in Montana, and I continued to work on spirochete-tick interactions with a primary focus on relapsing fever. Dr. Rosa's group focused almost entirely on the Lyme disease spirochete, looking at how these bacteria could adapt when infecting ticks versus mammalian hosts. Frank Gherardini’s projects involved several bacterial pathogens. He worked on Lyme disease projects and recruited a series of young scientists to work on Burkholderia. We had a fairly large Burkholderia program, but it was all done by his postdoctoral fellows, and when they left, work on these pathogens ended.

...

Schwan: Yes, I did go to Japan but basically there isn't much more to tell than that. I went over for a week and visited several laboratories. I gave seminars in Fukuyama and Sapporo. The fellowship was funded by the Japan Health Sciences Foundation, but I didn't live in Japan for any period or collaborate in a serious way. I had helped the fellow who put me up for the fellowship and hosted me. His name is Masahito Fukunaga [Dr. Masahito Fukunaga], and he's a wonderful fellow and now retired. He's the person who described Borrelia miyamotoi, which is the relapsing fever spirochete associated with hard ticks. And when he put his paper together in ‘94, he asked me if I would work on the paper and improve the English. I said, “Yes,” not knowing what I was getting myself in for. He sent me a draft that needed a lot of work. I basically rewrote the whole thing--well, it felt that way--and he acknowledged me for that at the end of the manuscript. I'm not a co-author and did nothing to warrant co-authorship. But the effort took me a couple months with everything else I was doing. It's a landmark paper now, given that Borrelia miyamotoi is known to be a human pathogen in Europe, Asia, and North America. There's a lot of interest in that disease and the ticks that transmit the spirochete.

| Span | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

Dr. Ben Mans (left) and Tom identifying ticks at Malaria Research and Training Center, Bamako, Mali; December 2007. |

Harden: Now let's turn to your research in Mali. Tell me when you went, why you went, and what you did while you were there.

Dr. Ben Mans (left) and Tom identifying ticks at Malaria Research and Training Center, Bamako, Mali; December 2007.

Schwan: Because of my two years in Kenya, I had developed a fascination and love of Africa. I knew that there had been papers describing tick-borne relapsing fever in Senegal, which is contiguous with Mali, so when I realized that our institute had an ICER, an International Center for Excellence in Research, at Bamako in Mali, I asked Dr. Zoon whether we might be able to start a project there. One primary goal was to determine whether or not some people may have been misdiagnosed with malaria and could actually have relapsing fever. Malaria is hyperendemic in Mali and quite seasonal. And yet some of the clinical manifestations of the two infections are quite similar. I approached Dr. Zoon and Dr. Barron about possibly doing a project there and they were both very supportive. The project would start with field work, to see if, by trapping animals and collecting ticks, we could find evidence of the spirochetes that cause relapsing fever.

...

The night we left—all the flights that one takes when one leaves Mali are late in the evening—we were at the airport in Bamako waiting to depart, and Dave got a text that said, “Another sample's coming in. We're going to test it here in the Bamako lab tomorrow." We got on the plane and left. When we got back to the States, we found out that the second sample was positive, and it turned out that there was another case, but Ebola never erupted in Mali like it did in other places. So, I didn't do much at all. I was over there on one trip to help if needed and I got an award. As I told several people, “I don't deserve this.” But there it is; I was on the list of awardees.

| Span | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

Donned with personal protective equipment (PPE) for handling human blood sample infected with Ebola virus, Bamako, Mali; November 2014. |

Harden: Between 2014 and 2017, you were retired from RML but continued to work as a halftime, re-employed annuitant. You also developed a class as an adjunct instructor at the University of Montana in Missoula. Tell me about this transition. Why did you decide to retire? What research did you want to continue to pursue? What you did for your course at the university of Montana.

...

The year before I “semi-retired,” I had been asked by a fellow at the University of Montana in Missoula if I might help develop a course with the parasitologist Bill Granath [Dr. Willard Granath, Jr.]. I asked Dr. Zoon about this and she was very supportive. It basically meant driving to Missoula twice a week and giving a 90-minute lecture for half a term. The classes I taught dealt with the epidemiology of vector-borne zoonotic diseases. I did that for five years. My last class was in the spring 2017.

| Span | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

Photograph replicating an historical picture of Dr. Willy Burgdorfer (insert lower right) working with ticks; January 2018. |

Harden: Since 2017, you've been a Special Volunteer in the Laboratory of Bacteriology. What have you been working on since then?

...

At home, I'm set up and working on a big project on tick salivary glands. I've got a microscope two feet away from me right now as we speak that actually belonged to the late Bill Hadlow [Dr. William Hadlow]. It was his personal microscope at home, and after Bill passed away, his daughter sold it to me. So, I'm still working, plugging away, trying to finish a few things, and learning something new each day.

| Span | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

With brother Mark (left) at the Minnesota River valley memorial honoring the Schwandt (later Schwan) family members killed on August 18, 1862, during the Sioux uprising. Tom’s great-grandfather, August Schwandt, was scalped and left for dead; only he and a sister survived. |

Harden: These are all the questions I have. Is there anything else that you would like to get on the record before we stop?

...