...

| Div | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

|

JV: While we were doing this, we had no idea of the impact on early pregnancy detection, abnormal pregnancy detection. In ectopic pregnancy, the levels of hCG usually start falling and they don’t rise as high as they do within a normal pregnancy.

However, measuring precise levels of hCG is exactly what the bioassays of the mid-twentieth century and the immunoassays of the 1960s could not do. The best test they had in 1970 was an immunoassay that could measure hCG but could not distinguish between hCG and luteinizing hormone (LH), another of the human gonadotropins that shares its biological characteristics

...

| class | usa-width-one-third |

|---|

...

.

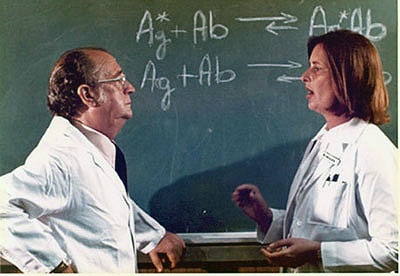

GB: Griff and I spoke. “Wouldn’t it be great to develop a new assay for hCG.” At that time Judy Vaitukaitis was immunizing rabbits with subunits of hCG and harvesting antibodies.

...

| Div | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

|

GB: So we went to the freezer. Griff Ross had serial samples from women with choriocarcinoma and we put those samples into the assay. Some of the women who were supposed to be cured actually still had hCG. We started to look at other types of cancers, too. Tom Waldmann at NCI also had a freezer full of blood samples from cancer patients, both single and serial samples. We put the samples through the assay, and found that 18% of the nontrophoblastic tumors showed levels of hCG. This was news: hCG was a tumor marker for non-trophoblastic tumors as well as trophoblastic tumors.

...

...

Working on an experiment, NICHD, c. 1971.

Research at NIH, as elsewhere, is a collaborative experience. Griff Ross’ group needed some basic research tools to do their studies, including, among other things, purified hormone and urine from post-menopausal women. These substances would be used for experiments as the scientists learned more about hormones and the human body. The group used hCG purified by NICHD grantee Robert Canfield, known as the CR preparation of hCG, for “Canfield-Ross.” For other research supplies, they turned to some unusual sources.

...

| Div | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

|

GB: We knew this would be a fantastic pregnancy test. We went to the government lawyers and said, “This is a technique that is going to be extraordinarily useful. Why not have NIH profit from it?” But since it was developed with public funds, the lawyers said no.

...

| class | usa-width-one-third |

|---|

...

In the 1970s, the researchers went on to other subjects. Vaitukaitis returned to Boston to spend a decade at the Boston University School of Medicine before returning to the NIH in 1986 to work with the division that would become the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR). She has served as Director of NCRR since 1993. Glenn Braunstein went to California, where he continues research on hCG and other reproductive hormones at Cedar-Sinai Medical Institute in Los Angeles. In his long and illustrious career at NIH, Griff Ross would attain the posts of chief of the Endocrinology and Reproduction Research Branch, clinical director of NICHD, scientific director of NICHD, and associate director of the Clinical Center.

...