...

| Div | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

What causes RMSF?

|

| Div | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

|

...

| Div | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

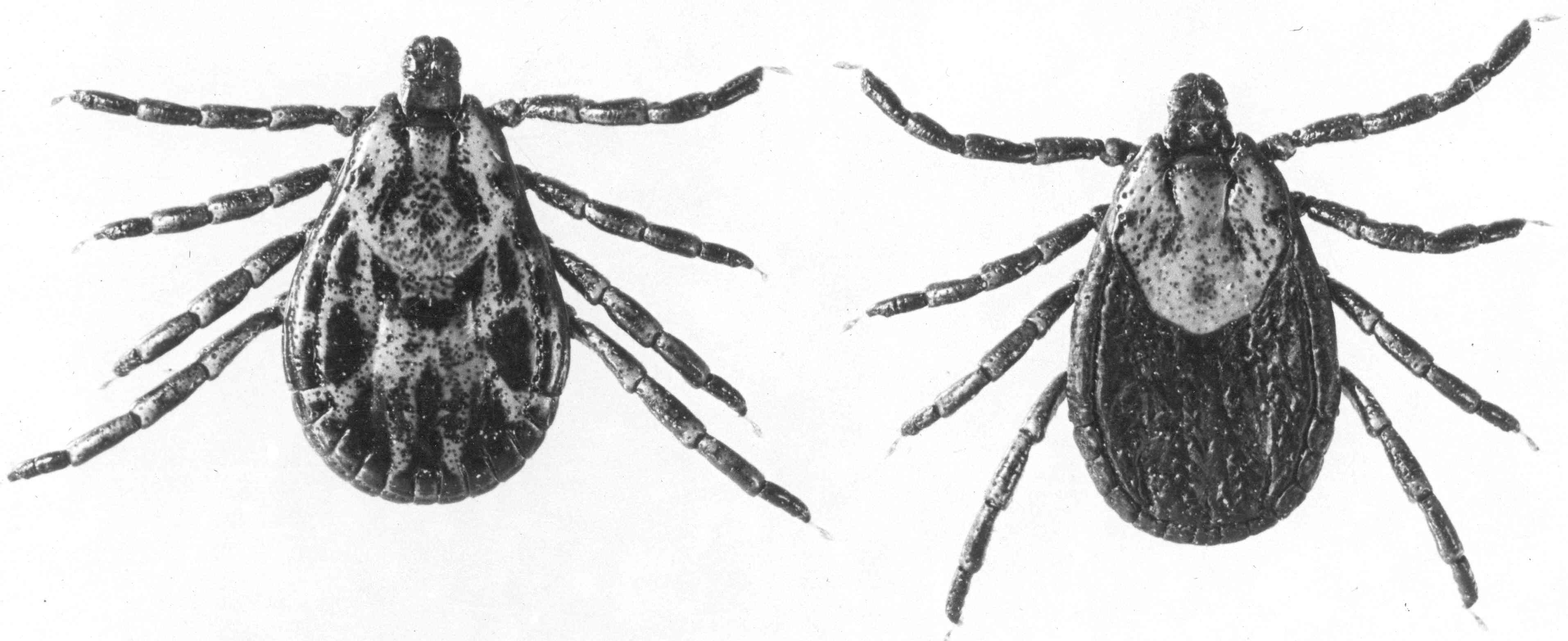

In spring, the nymphs once again attach to an animal and feed, drop to the ground, and digest their meals. This time they molt to adults, like these Rocky Mountain wood ticks, Dermacentor andersoni. They spend their second winter as unfed adults. The next spring they climb grass and bushes to attach to animals. But as adults, ticks mate as well as feed. This is when the ticks can get the Rickettsia rickettsii bacteria from the animals they feed on. Even though the bacteria don’t hurt the ticks, it infects all of their cells, and is passed on through the egg. The next generation of ticks will be infected. Images: Office of NIH History and Stetten Museum, 1454-58 |

...